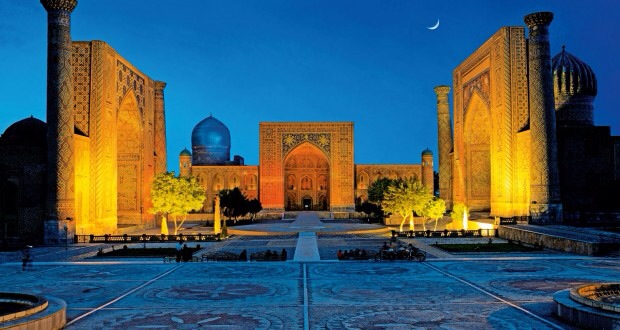

About a year before we left on this trip Andrew’s parents generously gifted us a subscription to National Geographic Traveller magazine. We enjoyed reading all of the issues, but one article in particular really stood out. It was called ‘On The Trail Of The Silk Road’ and was an overview of why you might want to travel to the Central Asian countries popularly known as ‘the Stans’ – Kazakhstan, Krgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. We found the whole article fascinating but the picture of the Registan in Samarkand just blew our minds and we instantly started thinking about how to work at least Uzbekistan into the plan.

The photo that inspired our travel to this Central Asian country [photo credit: National Geographic Traveller]

The photo that inspired our travel to this Central Asian country [photo credit: National Geographic Traveller]

Samarkand has been around for at least 2500 years and was a hub city on the Silk Road with all kinds of goods passing through from China, India and Persia towards Europe and vice-versa. In 1370 Amir Timur decided to make Samarkand his capital and the following decades saw the construction of majestic medressas, mausoleums and mosques. Nowadays it is a pleasant city with wide tree-lined streets and numerous fountains in between the historic sights.

Fountain at the end of Registan Street, in the evening it plays to a sound and light show

Fountain at the end of Registan Street, in the evening it plays to a sound and light show

Gur-E-Amir Mausoleum

The city is littered with impressive looking mausoleums but without doubt the most spectacular is the Gur-E-Amir Mausoleum which houses the remains of Amir Timur, his sons and grandsons. It was a two minute walk from our guesthouse so we passed it at least twice every day and struggled to stop ourselves taking more photos each time!

It was very difficult to stop ourselves from taking photos every time we walked past!

It was very difficult to stop ourselves from taking photos every time we walked past!

Inside, the walls and domed ceiling above the marble grave markers are covered in blue and gold paintings.

Amir Timur’s tomb is marked by the dark coloured stone in the centre of the picture

Amir Timur’s tomb is marked by the dark coloured stone in the centre of the picture

At night the mausoleum is illuminated

At night the mausoleum is illuminated

Registan

On our first afternoon in the city, Andrew, Jo and I walked up to Registan Square to catch a glimpse of the buildings which had inspired us all those months earlier. The only word that any of us were capable of for several minutes afterwards was “wow”! We visited the site several times during our stay including at sunrise and at night and the magnificent buildings never ceased to impress us.

Registan Square (from left to right): Ulugbek Medressa, Tilla-Kari Medressa and Sher Dor Medressa

Registan Square (from left to right): Ulugbek Medressa, Tilla-Kari Medressa and Sher Dor Medressa

A medressa is an Islamic school or college. Historically they taught a range of subjects to educate their religious leaders. We figured that Samarkand’s medressas were probably a bit like the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge which originally were principally engaged in educating priests.

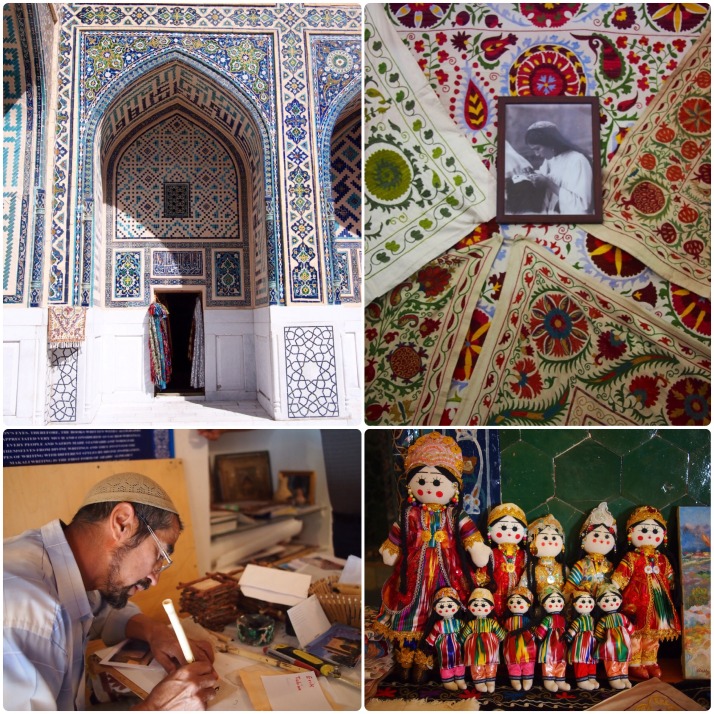

All of the buildings have been heavily restored and it was interesting to see photographs of how dilapidated they were at the beginning of the 20th century before work began. All three medressas have a similar structure; behind the elegant tiled facade is a courtyard surrounded on all sides by small rooms which would once have housed the students who were taught here. Nowadays most of the students’ cells house craftspeople and souvenir shops.

Souvenir shops in the Registan (clockwise from top left): scarves flutter beside a tiled shop entrance; display of Uzbek embroidery called suzani; costume dolls for sale; a calligrapher writing our names in arabic

Souvenir shops in the Registan (clockwise from top left): scarves flutter beside a tiled shop entrance; display of Uzbek embroidery called suzani; costume dolls for sale; a calligrapher writing our names in arabic

Our first stop was at the oldest, Ulugbek Medressa, built by (and named after) Amir Timur’s grandson, it was completed in 1420. Ulugbek was a renowned scholar, particularly famous for his astronomical observations. During his rule, Samarkand became an intellectual centre.

Tilla-Kari Medressa along the back of the square has a tree filled courtyard and also contains an elegant mosque with beautifully decorated walls and ceiling. One of the stalls inside the mosque was selling unusual ceramic Christmas decorations in traditional Uzbek patterns. We were very tempted but the vendor was asking a high price, in the end we walked away thinking we would see similar ones elsewhere but we never did.

Inside Tilla-Kari Medressa’s mosque

Inside Tilla-Kari Medressa’s mosque

On the eastern side of the square is Sher Dor (Lion) Medressa with its distinctive tiled lions (which look more like tigers to us) above the arch of its facade. They’re famous throughout the country and even feature on the UZS200 note.

Tilework in a courtyard niche of Sher Dor Medressa

Tilework in a courtyard niche of Sher Dor Medressa

Registan tile details including Sher Dor lion (top right)

Registan tile details including Sher Dor lion (top right)

As we were leaving, one of the security guards pulled Andrew aside and asked if we would like to climb one of the minarets of Tilla-Kari Medressa for an extra fee of 6,000 sum (about £1.20). We’d read that it is normal practice for the guards to offer extras like this and agreed on 15,000 sum for the three of us. Tilla-Kari’s minarets are much smaller than those of the other two buildings but we enjoyed the slightly different perspective that a couple of extra storeys provided as well as the thrill of doing something illicit!

Andrew climbing the spiral staircase inside the minaret of Tilla-Kari Medressa

Andrew climbing the spiral staircase inside the minaret of Tilla-Kari Medressa

Bibi Khanym Mosque

North-east of the Registan the Bibi Khanym Mosque towers over the surrounding market and park. It is named for Amir Timur’s Chinese wife and was once one of the Islamic world’s largest mosques. Somewhat crumbling in places, restoration work is ongoing. We were interested to see the huge stone Qur’an stand in the courtyard built for the massive Osman Qur’an which we saw in Tashkent.

Stone Qur’an stand [photo credit: Jo Harris]

Stone Qur’an stand [photo credit: Jo Harris]

Restoration work at Bibi Khanym Mosque (clockwise from top left): photograph of the mosque before work began; the interiors seem largely untouched; new tilework being prepared in one of the side mosques

Restoration work at Bibi Khanym Mosque (clockwise from top left): photograph of the mosque before work began; the interiors seem largely untouched; new tilework being prepared in one of the side mosques

Shah-i-Zinda and cemetery

Shah-i-Zinda, the Avenue of Mausoleums, translates as ‘Tomb of the Living King’ and refers to the central tomb which is thought to be that of Qusam ibn Abbas, a cousin of the Prophet Mohammed, and one of the first to bring Islam to Central Asia in the 7th century. This is a place of pilgrimage today and there were far more Uzbek visitors here than at the Registan.

Entrance to Qusam ibn Abbas’ tomb

Entrance to Qusam ibn Abbas’ tomb

After he made Samarkand his capital, Amir Timur started to bury his family and favourites here too resulting in a concentration of richly decorated mausoleums lining the approach.

Inside, some of them are rather austere with plain whitewashed walls while others are even more spectacular than their exteriors with delicately painted and tiled walls and ceilings.

Andrew photographing the beautiful interior of one of the mausoleums

Andrew photographing the beautiful interior of one of the mausoleums

Shah-i-Zinda details (clockwise from left): Jo photographing one of the mausoleums; arabic script in the tilework over one of the arches; bright blue tiles

Shah-i-Zinda details (clockwise from left): Jo photographing one of the mausoleums; arabic script in the tilework over one of the arches; bright blue tiles

At the far end of the row of mausoleums was the equally fascinating city cemetery. The grave stones are all carved with a portrait of the deceased along with their name and dates. It was interesting to see how the deceased were presented in their portraits (smiling, looking serious, or with full military medals) and we speculated about whether you had to have a photo portrait taken as you approached old age for the stonecarvers to work from. Transliterating the names was good practice for our Cyrillic reading skills too!

Old town

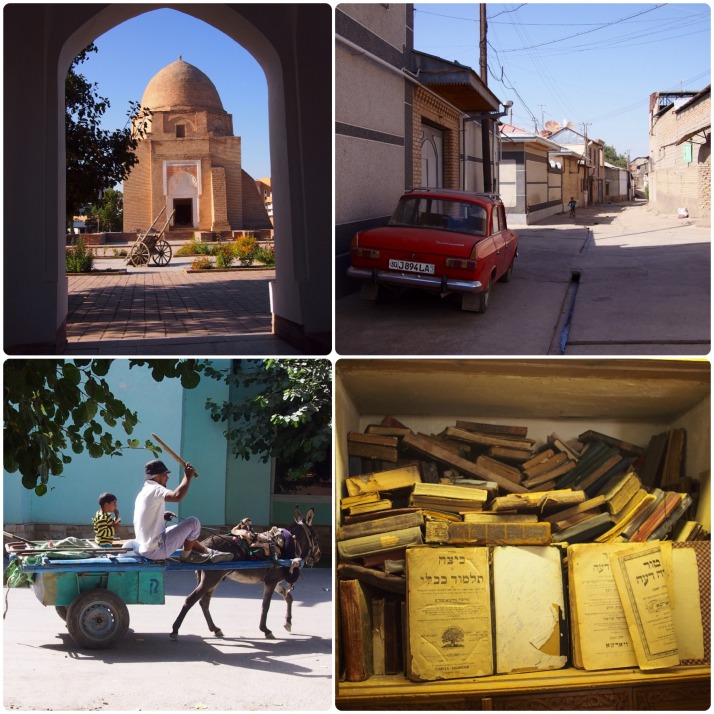

On a couple of occasions we ventured off the beaten tourist path into the narrow twisting streets of the old town. Traditional Uzbek houses are arranged around a courtyard so all that is visible from the street is a blank wall and a double door. Nevertheless we found plenty of life in the street and everyone was friendly and curious about where we are from. It was fun to stumble across little local mosques, mausoleums and even a synagogue in the old Jewish quarter.

Old town (clockwise from top left): Rukhobod mausoleum; old town street complete with Lada; Hebrew texts in the synagogue; we even saw an occasional donkey cart

Old town (clockwise from top left): Rukhobod mausoleum; old town street complete with Lada; Hebrew texts in the synagogue; we even saw an occasional donkey cart

Wine tasting

As a change from the historical monuments we followed a lead in the Lonely Planet to a wine factory in the newer part of town. We were expecting something quite basic so were surprised to be shown into a room hung with chandeliers which wouldn’t have been out of place in an English stately home.

Table set up for our wine tasting

Table set up for our wine tasting

The lady hosting the tasting explained that because of the hot sunny climate of Uzbekistan, the grapes were high in natural sugars particularly suiting them to dessert wine production. We tried a mix of 3 wines, 6 dessert wines, 2 cognacs and a balsam (herbal liquer) and were impressed with the quality. Unfortunately, production is limited at the moment so you’ll have to wait a while before you see Uzbek wines in your local off-licence.

Our tasting guide with the wines that we tried

Our tasting guide with the wines that we tried

We ambled off slightly sozzled and reinvigorated for another day of sightseeing…

Shakhrisabz

On our final day in Samarkand we took a day trip over the mountains to Amir Timur’s hometown and his second capital, Shakhrisabz. This city was once almost as impressive as Samarkand but nowadays is something of a backwater and its remaining monuments are in a pre-restoration state. The government has decided to relandscape the town centre to ‘prettify’ it and for no readily apparent reason have dug up the whole lot at once creating a horrifically dusty building site for residents and visitors to pick their way through, though somehow our feet looked much dustier than the locals’.

View from the mountain pass between Samarkand and Shakhrisabz

View from the mountain pass between Samarkand and Shakhrisabz

The building site that is currently Shakhrisabz centre with Ak-Saray Palace in the background

The building site that is currently Shakhrisabz centre with Ak-Saray Palace in the background

Shakhrisabz’s most important sight is the ruins of the Ak-Saray Palace. This was Amir Timur’s summer palace but all that remains is the craggy ruins of its entrance arch which stand at 38m tall and are separated by what would have been the 22.5m arch span. Given the scale of the entrance I can only imagine how impressive the rest of the palace must have been.

Jo and Andrew at the base of one of the Ak-Saray entrance arch pillars

Jo and Andrew at the base of one of the Ak-Saray entrance arch pillars

Crumbling but impressive ruins of Ak-Saray Palace

Crumbling but impressive ruins of Ak-Saray Palace

We wandered along the building site like main street, stopping in the dusty bazaar for somsas (Uzbek pasties) and tea for lunch. At the other side of town from the palace are some more monuments. The Dorut Tilyovat complex contains the exquisite Kok Gumbaz mosque and two equally beautiful mausoleums. The buildings are situated around a peaceful tree-filled courtyard which was a very nice respite from the dust.

Mausoleum of Sheikh Shamseddin Kulyal and Gumbazi Seyidan

Mausoleum of Sheikh Shamseddin Kulyal and Gumbazi Seyidan

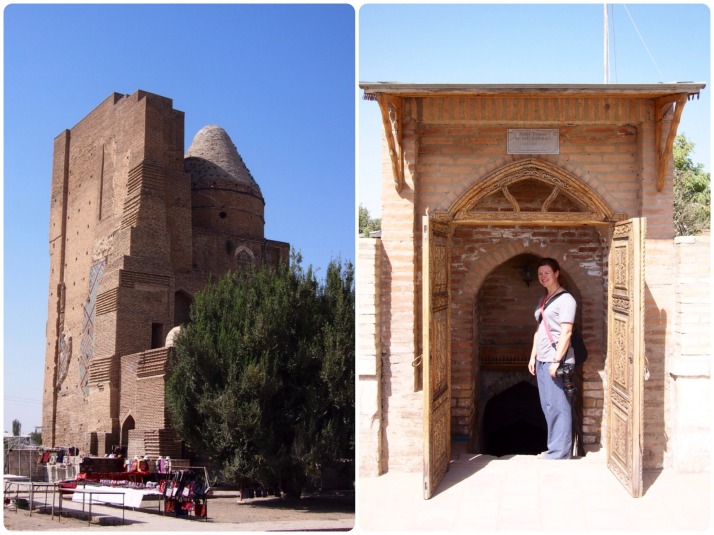

Behind Dorut Tilyovat is the Khazrati Imam complex with its modern working mosque and the dilapidated remnants of what was once a huge burial complex. There’s the tall Tomb of Jehangir with a conical roof which houses the remains of Amir Timur’s eldest son. Tucked away behind this is a set of stairs down to a small burial chamber which it is believed was intended for Amir Timur himself. Unfortunately he died in the winter and the pass over the mountains was closed by snow so he was actually buried in Samarkand.

Tomb of Jehangir; Jo at the top of the stairs to the Crypt of Timur

Tomb of Jehangir; Jo at the top of the stairs to the Crypt of Timur

There were far fewer tourists in Shakhrisabz than Samarkand and we found ourselves to be more than usual the subject of people’s curiosity. My curly hair in particular seemed to excite quite a lot of comment, we were talking to some ladies at a souvenir stall who, once they realised we weren’t going to buy anything, even asked if they could touch my hair!

two year trip

two year trip