A magician and a rasta walk into a bar…

Santiago de Cuba has a special place in our hearts. Our host Margarita arranged for a classic American car to pick us up from the coach station which was our first ride in one, as well as being one of the best casa chefs of our trip.

Our chariot awaits.. a lovely 1956 Plymouth Belvedere Sedan greeted us on our arrival in Santiago – what a welcome!

Parque Céspedes, the main square in Santiago de Cuba from the roof of Hotel Casa Granda

An eminently walkable city where the main pedestrian walking street and its parallel to the south links all of the parks, squares and central attractions, we found Santiago to be packed with loads of different things to see and do.

Walking around the city

On our first afternoon we took the Lonely Planet’s walking tour as a guide and headed out to get our bearings. Being just around the corner from the main Parque Céspedes we obviously went there first. Restored like so many main city squares in Cuba, the balcony of the white and blue Ayuntamiento that overlooks this square is where a certain Fidel Castro announced to his country and the world that the Cuban Revolution had succeeded.

The ‘Ayuntamiento’ in Santiago, which means local council. It’s here that Fidel announced the Cuban Revolution’s triumph

Just a block away is the Balcon de Velazquez which wasn’t at all what we’d imagined. I guess it’s called the balcony because it looks over the old French quarter of the city and down towards the bay and was once a small fort. We decided to forgo the small fee for taking photos until we’d taken a look first (which is free), and we’re glad we did as the views are likely better from any of the casas or private restaurants that have added 3rd or 4th floor rooftop dining areas that sadly obscure the view.

The Balcon de Velazquez. We’re glad we didn’t pay for the privilege of taking photos from the balcony itself as the view isn’t as interesting as the balcony building itself

Hotel Casa Granda

One rooftop view that would be difficult to obscure is the one from the Hotel Casa Granda which is also famed for its mojito making prowess, well, we didn’t need much more convincing than that to see for ourselves..

Great views from theHotel Casa Granda’s rooftop bar of the square and the Cathedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. Can you spot the impending rain in the background? We did!

About half-way down our drinks we saw dark clouds on the horizon and although it felt like the wind was blowing south and out to sea, the rain came east at us across the bay and everyone moved tables to shelter from the downpour. There wasn’t anything we could do but order another drink and sit it out. Oh well!

The rain meant we just had to stay put for another mojito. Happy days

Castillo del Morro

To give it its full name, Castillo de San Pedro de la Roca del Morro is a large fortification that was originally designed to protect the bay and city from the ravages of pirates, but by the time construction of the first fort was completed piracy was in decline so it never fulfilled its intended purpose. Subsequent alterations increased the size, and before its current incarnation as a museum it was used as a prison.

We enjoyed exploring the nooks and crannies of the labyrinthine Castillo del Morro

It’s about 10km south of the city and getting a taxi would have been easy, cost us about 15CUC (~£10), and have been boring. Instead, as we’d seen the large American trucks operating as private busses and found that the main station for them is on Avenue de Los Libertadores, we opted for adventure and it didn’t take long for one to stop that was heading about 1km shy of the fort. We did end up paying 10 times the local’s rate, but at 1CUC (70p) each it was still cheaper than a taxi.

The ‘camion’ or truck form of privately run public transportation in Cuba

The uphill 1km turned out to be a nice walk, though we needed to stop for a refreshing (and overpriced) lemonade in the tourist-tat gauntlet run before exploring the many levels, rooms and defensive walls of the Castillo. The latter offered some amazing views out across the Caribbean, back towards Santiago Bay and we could even see the international airport but the best views were looking down over the fort itself.

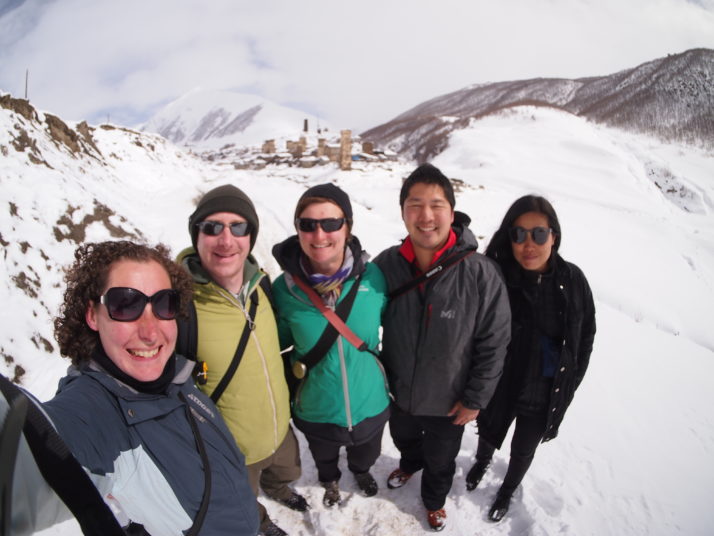

Us at the Castillo del Morro

We’d just about finished our exploration when the coach parties arrived, so we decided to take a shortcut to avoid the tourist stalls and ended up at the cove beach just north of the fort as another camion was about to leave. Not only were we able to flag it down, they charged us the local’s rate to return to town too!

Cementerio Santa Ifigenia

Julie has already written about the Cementerio Santa Ifigenia in our post about the cemeteries of Cuba. I’ll add here that it was one of our favourite sights in Santiago.

Moncada Barracks

A young and ideological Fidel Castro concluded that the corruption of Batista’s government couldn’t be eradicated through legal or populist support alone and decided on direct action. Specifically, a simultaneous assault on the two largest military barracks in the eastern Oriente region would allow room for a Revolutionary movement to gain support and work its way west towards Havana. Planned for the 26th of July 1953, the day after the annual street carnival to catch Batista’s army off guard, but as they were significantly outnumbered and outgunned, the rebels lost and ultimately most of them were killed or captured.

The former Moncada Barracks is a huge and imposing building

Fidel Castro, a qualified lawyer, stood trial and used his defence as the stage for his revolutionary message with a famous four-hour speech outlining his vision for an independent Cuba that ended with the line: “La historia me absolverá” – History will absolve me. Other factors such as the mistreatment of the rebel prisoners by the army, public pressure and interventions by a judge and the Catholic Church led to lenient sentences for all involved, and Fidel was given a 15 year prison sentence.

The museum is set up in the rooms attacked by Fidel’s rebels, though the scars of the fighting are reconstructions as the building was repaired and repainted shortly afterward

The following year, Batista’s government won an unopposed election that was criticised as fraudulent, and some politicians suggested that an amnesty for the Moncada perpetrators would be good for publicity. Batista agreed and in 1955 they were freed. How history could have been so very different.

The museum is nicely laid out, gave us a very good understanding of the Cuban Revolution, and at the same time tested our Spanish as very few of the explanations are in English. There’s a lot of emphasis on the mistreatment of the rebels by Batista’s troops accompanied by some pretty gruesome photos and supposed implements of torture, and the timeline pretty much stops at the Revolution’s triumph in 1959.

Gran Piedra and Cafetal la Isabelica

On a recommendation from our lovely hosts in Bayamo, we arranged a day trip to the Gran Piedra which literally translates as ‘large stone’. Our souped-up Lada taxi needed a few rest stops on the way to cool down from the hilly, poorly maintained roads, which meant we had chance to admire the scenery and stretch our legs.

Our souped-up Lada needed a couple of breathers to make it through the mountains to the Gran Piedra

The path that leads up to the Gran Piedra was through a pretty nice looking but empty hotel at the top of a hill that then has the ‘large stone’ perched on top of it! It’s easily the highest point for miles around and an easy walk along well maintained paths and steps – not at all as arduous as hiking up Pico Turquino!

We spotted a lots of birds on the short walk to the Gran Piedra

The Gran Piedra, or ‘large stone’ – how are we going to get up there?!

Made it! We weren’t expecting two shopping opportunities at the very top to accompany the spectacular views all the way to the Carribean.

How spectacular? How about this!

The Gran Piedra is the first stop on a recommended circuit that took us down a dirt road to the UNESCO recognised Cafetal la Isabelica, a restored two-storey mansion that was built by French slave-owning coffee growing emigrants from Haiti. The ground floor housed workshops for the creation and maintenance of the various tools the plantation required, while the top floor was home to the French owners. We didn’t pay for a guide, but as we were the only visitors there a bored one started contributing bits of history and information about the house, its restoration, and the layout of the plantation and it really added to our experience as there weren’t any explanations.

The drainage for the drying beds and water storage systems for the house were innovative for their time

Little details like the raw coffee was stored in the roof of the house away from the kitchens as the cooking smells affect their flavour brought the place alive for us.

They still grow a little coffee at the museum and as well as selling it as beans or grounds, they make a cup that rivals an Italian ristretto for strength!

Oh yes, the magician and the rasta.. there are any number of scams and annoyances targeting tourists to Cuba and Santiago is home to two colourful characters that saw us trying to write up our diaries in a bar and thought we might make for a couple of quid. The first was a magician, dressed in a smart tuxedo that looked 2 sizes too big for him, accompanied by a slightly inebriated sway reminiscent of the great Tommy Cooper. After a few card tricks and other sleight of hand tricks that were well done, he was adamant that his fiery finale would only work with a 10CUC note (~£7). Our point-blank refusal and the trio of small coins we gave him was easily worth the disdainful stare we got before he stood up and made an almost straight-line for the exit.

10 minutes later his seat is taken by a cheerful round rasta with a little English who claimed to play percussion in a band around the corner. During the next 30 minutes we learned his catchphrase of ‘peace and love’, his daughter’s name is Julia (what a coincidence!) and it’s her 9th birthday. Fascinating. He finally worked up to asking for money to buy balloons for his daughter’s party. Apparently, balloons are really expensive in Cuba. Well, we hope your birthday party wasn’t ruined without a contribution towards balloons Julia, if that’s your real name, if you exist at all.

two year trip

two year trip