Istanbul is full of interesting places to shop. Even if, like us, you’re not interested in buying lots of souvenirs there’s a lot to see. The walking tour that we took started at the Sahaflar Bazaar or book market, a small walled courtyard tucked behind Beyazit Square.

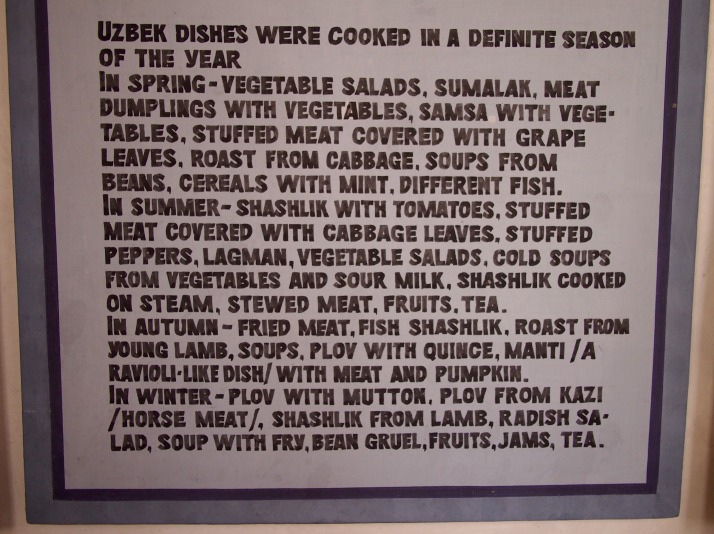

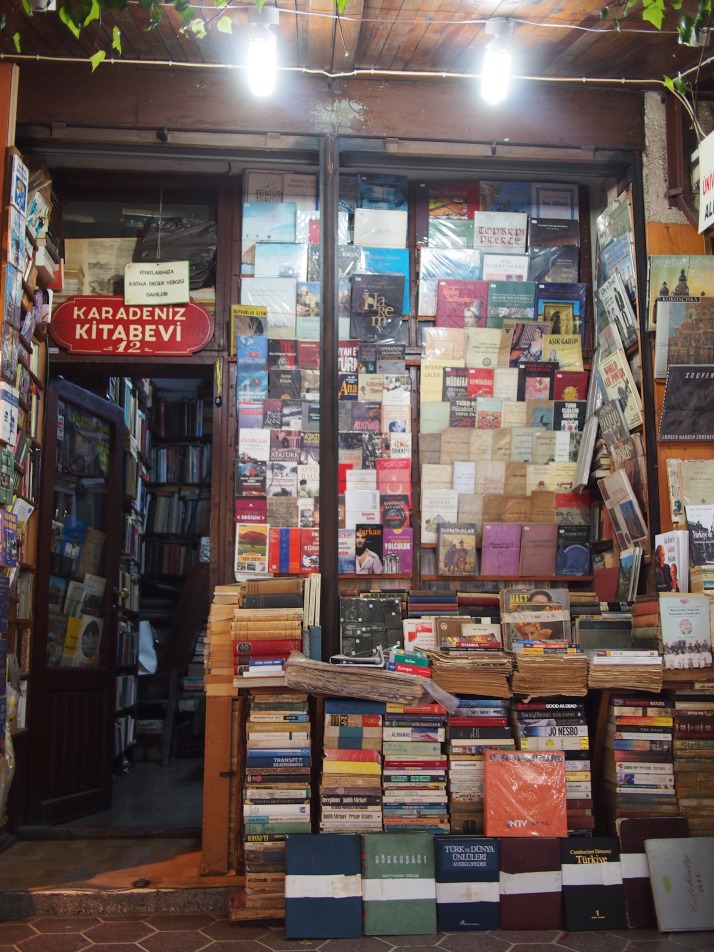

Shopfront in Sahaflar Bazaar, the market of second-hand booksellers

Shopfront in Sahaflar Bazaar, the market of second-hand booksellers

Grand Bazaar

We exited Sahaflar Bazaar through a gate which is just over the street from the most famous market in Istanbul, the Grand Bazaar. This is a vast covered complex which, even though it’s laid out in a grid, is incredibly disorientating once you’re inside. How big is it? Well, it contains more than 4000 shops so you really could lose yourself in here looking at everything that’s for sale!

The walkways through the Grand Bazaar are beautifully decorated

The walkways through the Grand Bazaar are beautifully decorated

My favourite shops were the ones selling the jewel like lamps

My favourite shops were the ones selling the jewel like lamps

Most of the shops are pretty small and so filled with merchandise that there’s no room for a kettle. Tiny tea shops send out runners with trays full of the typical tea glasses to keep everyone in the market going.

Most of the shops are pretty small and so filled with merchandise that there’s no room for a kettle. Tiny tea shops send out runners with trays full of the typical tea glasses to keep everyone in the market going.

In the centre of the market is an area called the Old Bedesten. It is one of the original structures of the market dating back to the early 15th century. Historically it has housed the most precious of the market’s wares as it can be securely locked at night. Nowadays it is still home to some swanky looking jewellery and antique shops.

Old Bedesten (clockwise from top left): the heavy doors can be locked at night; there were lots of antique pipes of interesting designs; tiled fountain; display of beads

Old Bedesten (clockwise from top left): the heavy doors can be locked at night; there were lots of antique pipes of interesting designs; tiled fountain; display of beads

Gold shops feature heavily in and around the Old Bedestan

Gold shops feature heavily in and around the Old Bedestan

It wouldn’t be Turkey without someone trying to sell you a carpet. This seller had set up shop outside one of the Grand Bazaar’s gates but there were plenty inside too

It wouldn’t be Turkey without someone trying to sell you a carpet. This seller had set up shop outside one of the Grand Bazaar’s gates but there were plenty inside too

The most surprising sight of the day was seeing gold dummies in a gold shop’s window display!

The most surprising sight of the day was seeing gold dummies in a gold shop’s window display!

Shopping streets

The area running from the Grand Bazaar down the hill to the Galata Bridge is a warren of narrow streets filled with shops. As in the Grand Bazaar (and many other market areas we’ve visited in Asia – Hanoi and Hong Kong to name just two) shops are grouped roughly according to the product they’re selling so we found streets full of underwear and pyjamas followed by streets of cookware and so on.

I liked looking up and noticing the ancient architecture of the buildings housing the modern shops

I liked looking up and noticing the ancient architecture of the buildings housing the modern shops

Many of the alleys are too narrow for trucks to access so porters run to and fro with massive loads, usually on trolleys but occassionally on their backs

Many of the alleys are too narrow for trucks to access so porters run to and fro with massive loads, usually on trolleys but occassionally on their backs

The walking tour directed us into the courtyards of several hans. These are old commercial buildings which were used to store a merchant’s goods and for merchants from distant places to stay in safety, they’re also known as caravanserais. Each han had buildings arranged around one or more courtyards with strong gateways to keep the goods safe. Several of the ones we saw were in a pretty poor state of repair but were often still used for commerce containing either shops or storage.

Courtyard of Kürçü Hanı where we found dozens of shops filled with knitting wools, buttons and haberdashery

Courtyard of Kürçü Hanı where we found dozens of shops filled with knitting wools, buttons and haberdashery

Turkish coffee is thick and strong and served in tiny cups. It’s made by boiling the coffee grounds with sugar and water in copper pots like these which we saw on a street full of metalwares

Turkish coffee is thick and strong and served in tiny cups. It’s made by boiling the coffee grounds with sugar and water in copper pots like these which we saw on a street full of metalwares

Rüstem Paşa Mosque

At the edge of the shopping streets is the Rüstem Paşa Mosque. We found the mosque easily enough, but finding a way in was not so straightforward. The mosque is built above the shops below and is accessed via two unobtrusive staircases between the merchandise.

Courtyard of Rüstem Paşa Mosque

Courtyard of Rüstem Paşa Mosque

The most notable feature of the mosque are the beautiful tiles which cover large portions of the walls as well as the columns, mihrab and mimber

The most notable feature of the mosque are the beautiful tiles which cover large portions of the walls as well as the columns, mihrab and mimber

Spice Market

The final stop on our market exploration was the Spice Bazaar. Originally a part of the Yeni Cami mosque complex this market is an L-shaped block of shops selling not only spices, but Turkish Delight (lokum), nuts and dried fruit, along with other fancy foodstuffs as well as a generous sprinkling of souvenirs.

Spices for sale at the Spice Bazaar

Spices for sale at the Spice Bazaar

There are far more versions of Turkish Delight available in Istanbul than the pink one that we’re used to, lots of them contain nuts or pieces of dried fruit

There are far more versions of Turkish Delight available in Istanbul than the pink one that we’re used to, lots of them contain nuts or pieces of dried fruit

Inebolu Market

As a complete contrast to the bustling streets and souvenir stalls around the Grand Bazaar, the next day we headed to the Sunday Inebolu farmers market at Kasımpaşa. Here we didn’t see any other tourists, just lots of locals stocking up on seasonal fresh vegetables, bread and cheese.

As it’s autumn mushrooms were everywhere with whole stalls dedicated to them

As it’s autumn mushrooms were everywhere with whole stalls dedicated to them

Fresh produce (clockwise from top left): green peppers; chestnuts ready for roasting; a cascade of green; pretty baskets of eggs

Fresh produce (clockwise from top left): green peppers; chestnuts ready for roasting; a cascade of green; pretty baskets of eggs

It’s customary to just approach the olive stall and help yourself to a sample from each tub until you find the one that you would like to buy!

It’s customary to just approach the olive stall and help yourself to a sample from each tub until you find the one that you would like to buy!

We bought a large bag of the mushrooms and a very dense loaf of bread – what better way to use them up than garlic mushrooms on toast?

We bought a large bag of the mushrooms and a very dense loaf of bread – what better way to use them up than garlic mushrooms on toast?

two year trip

two year trip