Buddhism and Shintoism

First, a quick primer about religion in Japan. Most Japanese practice both Shintoism and Buddhism. Shintoism is the native religion and celebrates life, the many shrines are dedicated to various gods of the natural world, for example, the god of rain, or the god of the mountain. When babies are born they are celebrated at the Shinto shrine, and its also where farmers make offerings and prayers for a good crop or favourable growing weather. Buddhism, which arrived via China and Korea, is practiced alongside, and has many rituals relating to death so funerals are conducted at the Buddhist temple. Therefore it is said that Japanese are born under Shintoism and die under Buddhism. However, the two religions are so entwined that it’s sometimes difficult to know where one ends and the other begins, Shinto symbols such as torii gates or shrines are often found at Buddhist temples and vice versa.

A bright red Shinto torii gate with guardian dogs in the middle of the Buddhist Danjo Garan Temple Complex

A bright red Shinto torii gate with guardian dogs in the middle of the Buddhist Danjo Garan Temple Complex

Koyasan is a sacred place for Buddhism in Japan and the home of the Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism. Its founder, Kobo Daishi, established a religious community here in 816 AD and is buried here, or rather his followers believe that he has entered a state of meditation in his tomb to await the arrival of the future Buddha.

The last stage of the journey to Koyasan is in a cable car

The last stage of the journey to Koyasan is in a cable car

Staying in a temple, or not, in Koyasan

Many visitors stay in one of the 50-60 temples around the town and we considered doing that, but it’s fairly expensive (prices start at £60 per person per night half board) and so we chose the budget alternative – a capsule guesthouse! Koyasan Guesthouse Kokuu is small and perfectly formed, it’s run by husband and wife team Ryochi and Yuri, and when we arrived Ryochi sat down with us and a map for about 10 minutes managing to answer all of our many questions without us having to actually ask them! Our capsule bedrooms were surprisingly spacious and very comfortable, and Yuri cooks up a mean curry which we enjoyed for our dinner with a flask of hot sake.

Koyasan Guesthouse Kokuu: Inside a capsule, guesthouse corridor, chicken curry and hot sake for dinner

Koyasan Guesthouse Kokuu: Inside a capsule, guesthouse corridor, chicken curry and hot sake for dinner

Some of the things we wanted to experience which are typically included as part of the temple-stay experience were the opportunity to witness the monks’ chanting in the morning ceremony, the chance to learn more about the religion and monks’ lives, and trying the Buddhist vegetarian cuisine called Shojin Ryori. Ryochi managed to construct an itinerary for us that covered all of those bases as well as seeing the main sights. First up was lunch at Sanbo where we tried a couple of the Shojin Ryori set menus. It was a diverse and interesting feast with lots of different kinds of tofu, delicious mountain vegetables, and lots of sesame seeds. Yum.

Shojin Ryori meal, before and after!

Shojin Ryori meal, before and after!

Kongobu-ji Temple

Next we set off to visit Kongobu-ji Temple, the administrative headquarters of Koyasan Shingon Buddhism. Set around the entrance courtyard are the beautiful main hall with its thatched roof (complete with fire buckets on top), a smaller thatched building previously used to store documents and a belfry with an unusual outward curving wall described on the information board as a ‘skirt’.

Kongobu-ji Temple (clockwise from top): Main temple building (note the large wooden buckets on the roof ridge), a cup of green tea and a rice cracker are included in the admission fee, you need to change from your outdoor shoes into slippers to enter the temple, beautiful carvings on the gable

Kongobu-ji Temple (clockwise from top): Main temple building (note the large wooden buckets on the roof ridge), a cup of green tea and a rice cracker are included in the admission fee, you need to change from your outdoor shoes into slippers to enter the temple, beautiful carvings on the gable

One reason that we visited was that this temple has the largest Zen rock garden in Japan. We found the rock garden a little disappointing as it wasn’t possible to see all of it and there wasn’t room to sit and contemplate around its edge. The leaflet explained that it represented two dragons flying through the clouds, but some idea of the meaning behind the forms would have been good too.

Banryutei rock garden

Banryutei rock garden

However, the stunning painted screen doors dating from the 16th century which are in the rest of the temple more than made up for the slight disappointment of the rock garden. Amongst other things, they show scenes from Kobo Daishi’s life as well as flowers and birds of the four seasons.

Screen doors painted with cranes

Screen doors painted with cranes

Okunoin Cemetery

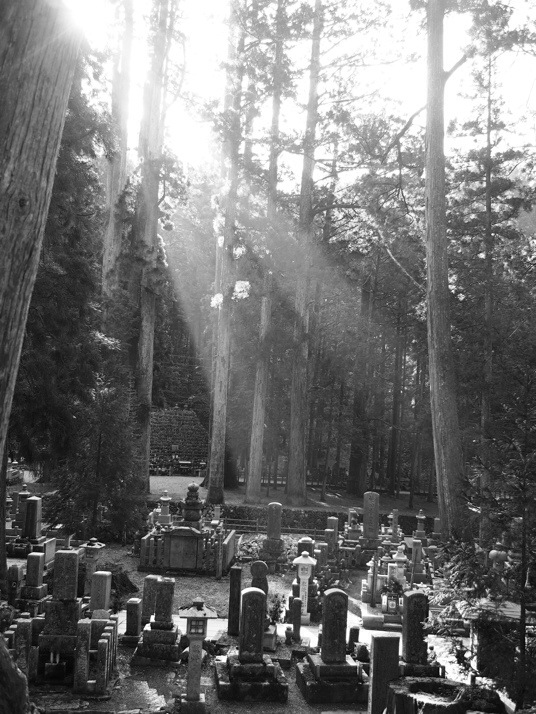

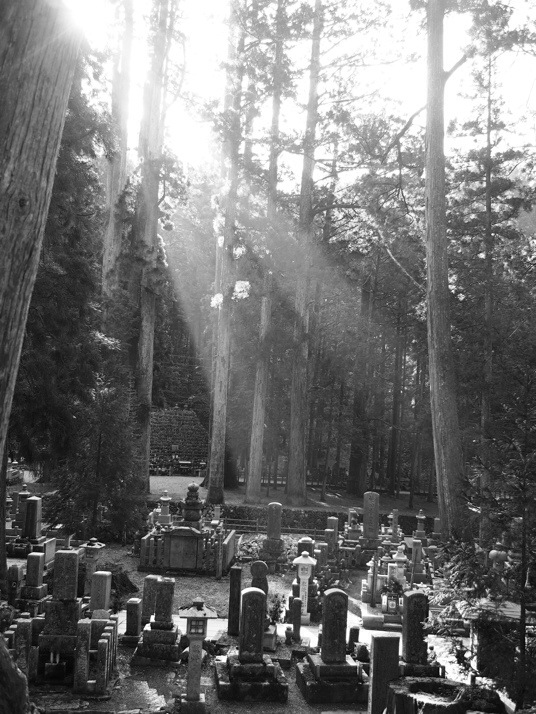

I didn’t quite know what to expect when we read all the superlatives applied to Okunoin Cemetery, but it really is as atmospheric as all the reviews suggest. I think I would even say that it’s one of my favourite places of the trip so far, certainly from a photography point of view.

Sunbeam shining through the cedar trees onto Okunoin cemetery

Sunbeam shining through the cedar trees onto Okunoin cemetery

The cemetery itself is vast with over 200,000 graves. Our introduction to it was on a night tour guided by a Buddhist monk from Ekoin temple called Nobu (organised through Ryochi at the guesthouse) and it was a little strange to be seeing it for the first time in the dark. Nobu was an excellent guide, he gave us a lot of background information about the cemetery and about Buddhism in Japan, interspersed with scary legends and cries of ‘careful, steps!’

Stone lanterns light the path through Okunoin cemetery at nighttime

Stone lanterns light the path through Okunoin cemetery at nighttime

Two of the most obvious and useful things that he explained were the gorinto shape of most of the gravestones and the significance of the jizo statues. The gorinto is a column of five shapes representing (from bottom to top) earth, water, fire, wind, and space or void. Together with consciousness these elements form the whole universe.

Gravestones – mostly gorintos but we saw many different ones including a space rocket and a Möbius strip!

Gravestones – mostly gorintos but we saw many different ones including a space rocket and a Möbius strip!

The small statues with bibs are jizo, they sit between the living and dead worlds, and their purpose is to guide spirits from life to death. They are often found at the site of deaths (e.g. by a roadside or forest trail). The bib should be red, it signifies the fire required to purify the spirit before crossing to death.

Jizo statues

Jizo statues

The mausoleum of Kobo Daishi is the most sacred place in the cemetery. Nobu took us behind the lantern hall to stand in front of the mausoleum. Here he told us the story of Kobo Daishi’s eternal meditation and chanted the Heart Sutra which was a beautiful end to the tour.

The lantern hall was also where we were able to see the morning chanting. Ryochi had told us that it was OK to leave quietly part way through but we ended up sitting and listening to the whole of the one hour ceremony with four monks chanting and a head monk making ritualistic sounds with a drum and gong, it was a mesmerising and otherworldly experience. After the ceremony finished at 7am we wandered the almost empty cemetery.

The path through the cemetery is lined with huge Japanese cedar trees. Their average age is 200-600 years, but some are as old as 1000 years.

The path through the cemetery is lined with huge Japanese cedar trees. Their average age is 200-600 years, but some are as old as 1000 years.

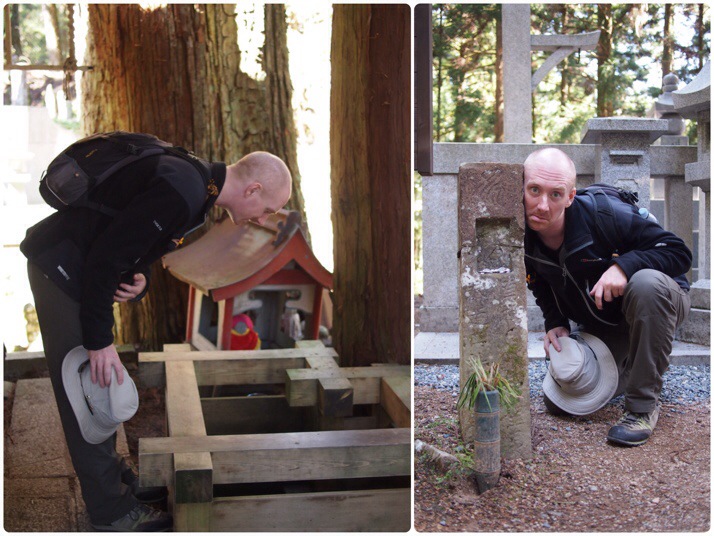

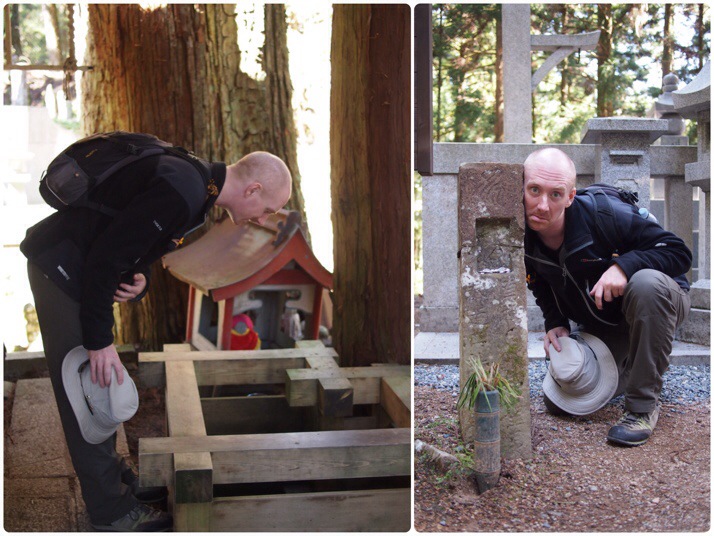

As you might expect with a cemetery, there are a few superstitious stories connected with Okunoin. There is a well in the centre where it’s said if you can’t see your reflection in the water you’ll die within three years (I’m pleased to report that we were both able to see our reflections), a gravestone which if you put your ear against it you can hear the cries in hell (fortunately that one didn’t work…) and a stone which pilgrims try to lift onto a shelf – the heavier the stone the more sins you have (we couldn’t try it as the building containing it was boarded up).

Andrew looking for his reflection and checking if he could hear the cries in hell

Andrew looking for his reflection and checking if he could hear the cries in hell

Many companies also have plots, we spotted a familiar logo amongst them

Many companies also have plots, we spotted a familiar logo amongst them

Danjo Garan Complex

The Danjo Garan complex is the site of the first monastic constructions here in the early 9th century although no original buildings remain (building your temples from wood and thatch leads to a high probability of destruction by fire). Along with Okunoin it is one of the most important places in Koyasan. There’s no entry fee to just wander around (you only need to pay to enter the buildings which are open to the public) and it was a good place to see the traditional wooden architecture and thatched roofs up close.

Kobo Daishi planned for the Konpon Daito (Great Pagoda) to be the centre of his monastic complex

Kobo Daishi planned for the Konpon Daito (Great Pagoda) to be the centre of his monastic complex

Nyoninmichi

Until the late 19th century women were not allowed to enter the town area of Koyasan and so female pilgrims followed a trail circumnavigating the town with dedicated women’s temples on each of the access roads. Nowadays the trail is set up for hikers and it’s a nice way to get a different perspective on the town as well as some spectacular views if you’re lucky enough to get clear weather as we were. The total length of the path is 15.5km but it’s possible to break it down into smaller sections.

Julie in front of the 25m high Daimon (Great Gate) at the western edge of the town

Julie in front of the 25m high Daimon (Great Gate) at the western edge of the town

On our first afternoon we climbed from the Daimon (Great Gate) up between torii gates to the summit of Mt Betendake. It was quite steep and in places the steps were very uneven but we got spectacular views across to the Inland Sea (about 20km away we think) and it was nice to be up above and out of the bustle of the town for a while.

The view to the coast – you can see the sea glistening on the right of the picture behind the trees

The view to the coast – you can see the sea glistening on the right of the picture behind the trees

The following day we decided to tackle the southern portion of the women’s pilgrimage route about 5km, or just over 3 miles, from the guesthouse to the opposite end of town, ending by the Daimon. Again, we met very few other walkers so most of the time it was just us and the rustling of skinks (small lizards) in the dry leaves with occasional glimpses across the valleys and mountains.

Steps up through the trees, toriis line the path up to Mt Betendake, a small skink with a very bright tail

Steps up through the trees, toriis line the path up to Mt Betendake, a small skink with a very bright tail

Us on the trail

Us on the trail

Koyasan was an excellent stop on our itinerary. I’m sure that a stay in one of the temples would be very rewarding but we didn’t feel that we’d missed out on anything by staying in cheaper accommodation, we just wish that we’d booked two nights instead of one!

Bags of ash awaiting collection on a street corner in Kagoshima

Bags of ash awaiting collection on a street corner in Kagoshima Sakurajima billowing smoke, seen from the cruise ferry

Sakurajima billowing smoke, seen from the cruise ferry Us at Yunohira Observatory

Us at Yunohira Observatory Yunohira Observatory (clockwise from top): View across the bay to Kagoshima, aerial view of the three craters in the visitor centre, one of the heart shaped stones once we’d cleared the ash away

Yunohira Observatory (clockwise from top): View across the bay to Kagoshima, aerial view of the three craters in the visitor centre, one of the heart shaped stones once we’d cleared the ash away From Karasujima we walked the 3km trail back to the port town to end the day with a soak of our feet in the public foot bath

From Karasujima we walked the 3km trail back to the port town to end the day with a soak of our feet in the public foot bath Deserted sea front at Ibusuki

Deserted sea front at Ibusuki Rows of spa goers buried in sand at Sunamushi Kaikan Saraku

Rows of spa goers buried in sand at Sunamushi Kaikan Saraku Staff shovelling sand over Julie

Staff shovelling sand over Julie Buried up to our necks! You wrap a small towel around your head to protect your head and neck from the heat

Buried up to our necks! You wrap a small towel around your head to protect your head and neck from the heat Andrew escaping from under the sand

Andrew escaping from under the sand

two year trip

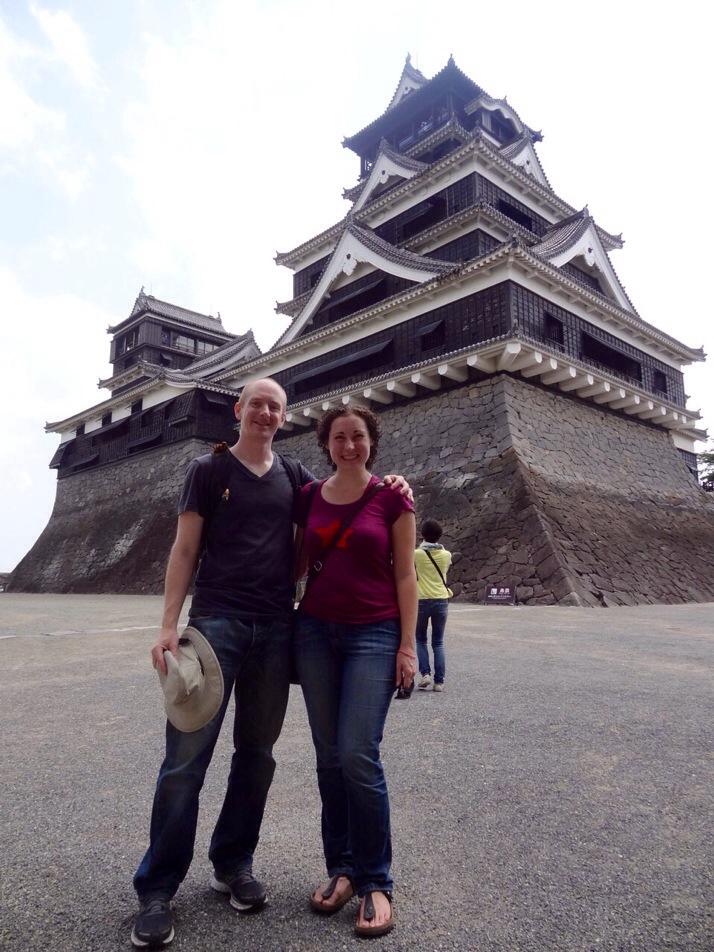

two year trip Us in front of the main keep of Kumamoto Castle

Us in front of the main keep of Kumamoto Castle Massive stone walls protect the castle

Massive stone walls protect the castle The Shokun-no-ma room in the guest hall of the Honmaru Palace reconstruction is extravagantly decorated in gold leaf and bright colours. Even the ceiling is covered with gold and painted with flowers (top right).

The Shokun-no-ma room in the guest hall of the Honmaru Palace reconstruction is extravagantly decorated in gold leaf and bright colours. Even the ceiling is covered with gold and painted with flowers (top right). There are several wells around the castle grounds which were used to provide drinking water during the siege period. This one was deep!

There are several wells around the castle grounds which were used to provide drinking water during the siege period. This one was deep! Looking across the pond towards the carefully manicured slopes of ‘Mt Fuji’ (towards the left of the picture)

Looking across the pond towards the carefully manicured slopes of ‘Mt Fuji’ (towards the left of the picture) Suizenji garden (clockwise from left): Well, teahouse across the pond, heron, Arum lilies

Suizenji garden (clockwise from left): Well, teahouse across the pond, heron, Arum lilies Shrine in the grounds of Suizenji Garden

Shrine in the grounds of Suizenji Garden Us with a Kumamon cut-out near Suizenji Garden

Us with a Kumamon cut-out near Suizenji Garden