Georgia is a mountainous land. There’s a low, flattish strip running from the Black Sea in the west to the Azerbaijan border in the south-east, but everywhere else is high ground with the mighty Caucasus mountains forming the country’s northern border with Russia. Visiting at the end of March we weren’t sure whether the snow would have melted and how accessible the mountains would be but we wanted to try to get to them.

Into the mountains! There was still a lot of snow as we crossed the Jvari pass before dropping down a little into Kazbegi

View from our guesthouse, Homestay Lela and Mari. We originally thought that Mt Kazbek was the snowy section to the right of the monastery, and then we saw the peak poking out from the clouds above!

Kazbegi (clockwise from top): the River Terek runs through the town; Soviet era mural adorning the end of a building in the centre; parts of the town are looking a bit run down including this now defunct cable car station

On our second morning in Kazbegi, Andrew got his camera set up to take a time-lapse of the sunrise.

After breakfast we set off to hike up to the Tsminda Sameba (Holy Trinity) monastery which we’d been admiring from below since the previous afternoon. We refused the many offers of ‘taxi?’ as we walked through the town, crossed the river and passed through the opposite village of Gergeti. The hike was steep but not difficult and with a few pauses to catch our breath admire the spectacular view we made it up to the monastery in about an hour from the valley floor.

Cows beside the path as we pass through Gergeti village on the way to the monastery

Andrew, Jo and I in front of the postcard perfect view of Gergeti Tsminda Sameba church

The Gergeti Tsminda Sameba monastery really does have a stunning location

On our second day in Kazbegi we walked along the valley to the village of Pansheti. On the way we passed this swimming pool fed from a mineral spring

We took the afternoon marshrutka back to Tbilisi in time to catch the overnight train to Zugdidi. We love sleeping in the rocking motion of a slow train but this one would have been a bit more comfortable if they’d turned the heating down a few notches

Mestia and its distinctive defensive towers

Svan towers (clockwise from left): the tower entrance is part way up the side to aid with defence; Jo climbing up one of the ladders, stone slabs would be used to close these holes in case of attack; only the top floor of the tower has windows

Although Mestia is at roughly the same altitude as Kazbegi, around 1500m, the sunny spring weather that we’d experienced in the eastern mountains didn’t quite seem to have arrived here yet. There was still snow on the ground and on our second day we were more or less snowed in as the fluffy flakes fell continuously from early morning to late evening. We ventured out for a walk to the cathedral (locked) and for lunch at a local cafe but mostly we just holed up in our guesthouse around the cosy wood burning stove.

Holed up in the guesthouse on a snowy day in Mestia

Fortunately by the following morning the sun had appeared and was starting to lift the clouds from the mountains. We’d arranged a trip to Ushguli, a UNESCO listed village further into the mountains with Vakho, our guesthouse owner’s brother. Also joining us were a Korean woman and a Japanese man who we’d met in town. It’s a rough road passable only by 4WD vehicles even in the summer and the 47km (29 miles) takes over 2 hours to drive. We reached a point where no other vehicles had driven and were cruising along downhill when suddenly a Russian made jeep flew around the corner ahead of us. CRUNCH! There was nowhere for us to go and the front corner and headlight unit of our Mitsubishi was caved in by the impact.

Crash on the snowy road to Ushguli

Luckily no-one was hurt and the engine wasn’t damaged so after a short while we were back on our way though Vakho was understandably upset at the damage which would likely cost him significantly more to fix than the 200GEL that we were paying him for the day’s excursion. There’s no car insurance here and the other vehicle’s owner didn’t seem to be overly concerned about helping out though technically it was his fault as he was driving uphill.

The previous day’s snow made the view from the road to Ushguli even prettier

The community of Ushguli stands at the foot of Mt Shkhara, Georgia’s highest peak, and is made up of five villages, one of which was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1996 as an “exceptional example of mountain scenery with medieval-type villages and tower-houses”. At an altitude of between 2060 and 2200m it also lays claim to being the highest permanently (i.e. year round) inhabited settlement in Europe. It must be a difficult place to live, bitterly cold in the winter (it was bad enough in late March), two hours on a bad road to the nearest small town, and five or more to anything bigger, the people must be hardy and self-sufficient in ways that are difficult for us to imagine.

The villages of Ushguli, in the foreground UNESCO listed Chazhashi, with Chvibiani behind

One Svan culinary specialty is the kubdari, similar to the cheese-filled khachapuri found in the rest of Georgia, but stuffed with seasoned meat. In Ushguli we got an impromptu cooking lesson from a cafe owner as we watched her make pies for our lunch. I suspect that getting the filling to stay neatly inside the dough is not nearly as easy as she made it look. Once made, the kubdari were cooked on top of and then inside the traditional wood-fired stove which is the heart of every Svan home and kitchen.

Cafe owner making kubdari, Svan meat pie, in Ushguli

After lunch, Vakho and the cafe owner scrambled the security guard and museum keeper to open the small ethnographic museum up for us. Located in a fat tower in Chazhashi, it houses treasures from Ushguli’s seven churches including gold and silver chalices, icons and crosses as well as jewellery and drinking horns.

Ushguli ethnographic museum

Emerging from the museum we trudged through the snow a little further along the street when we heard loud barking and saw an enormous Caucasian shepherd dog bearing down on us. A woman shouted at him but we beat a hasty retreat all the same. The dogs in the streets of both Ushguli and Mestia are quite intimidating. Not so bad if it’s a cute waddling sausage dog, but others are descended from the mountain dogs bred to protect the sheep from wolves and bears and could do quite a bit of damage if they felt so inclined. Locals told us that they are generally safe as the dogs have learnt that tourists will give them food but I didn’t enjoy having a pack follow us around especially as we had no intention of feeding them.

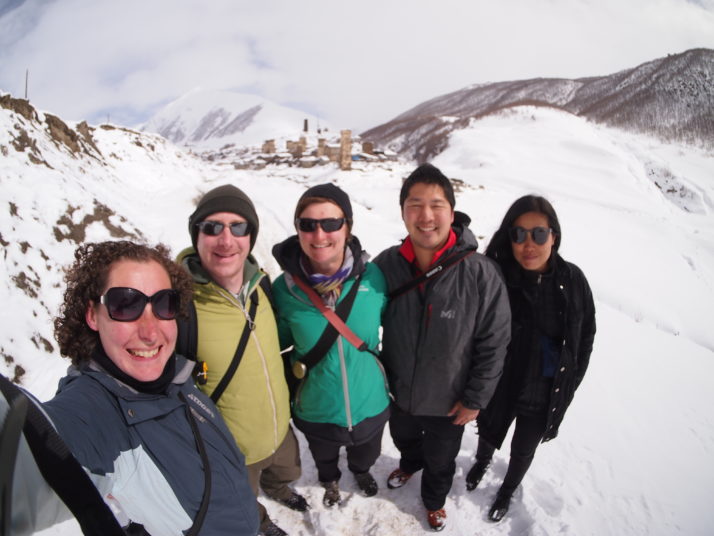

Our tour group in Ushguli (left to right): Julie, Andrew, Jo, Masato, Hyunja

Feral dogs aside, the mountains were a highlight of the trip for all of us and we vowed to return in the summer for some hiking!

two year trip

two year trip