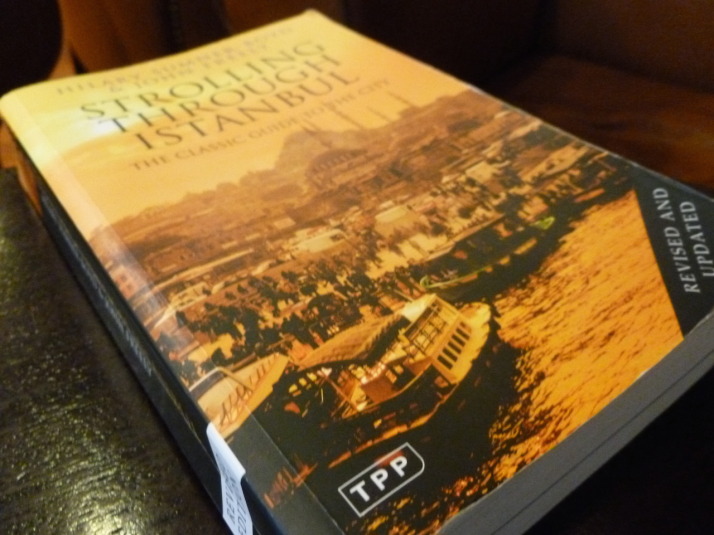

Continuing our strolling explorations through Istanbul, we popped our heads into Sultan Ahmet Camii, known in English as the Blue Mosque, which is also the starting point for the day’s walking trail which took us downhill to the edge of the Marmara Sea (chapter 6, page 107).

Sultan Ahmet Camii aka The Blue Mosque

Sultan Ahmet Camii, also known as The Blue Mosque

The Sultan Ahmet Camii is the most famous purpose-built mosque in Istanbul. I say it that way because, in a “keeping up with the Joneses” kind of way, it sits next to the larger, grander Hagia Sophia. Founded by Sultan Ahmet I, he instructed his architect – a student of the famous Sinan – to build a mosque that surpassed the beauty of Hagia Sophia. There are a few nice tales about its construction.. firstly, the young Sultan was so keen to see it completed that he often pitched in himself; and secondly that when it was unveiled as having 6 minarets rather than 4, Sultan Ahmet was accused of being too self-aggrandising because Mecca was the site of the only other 6-minareted mosque. His solution was to pay for a 7th minaret in Mecca.

Sultan Ahmet Camii, as viewed from its courtyard on an overcast day. The other two minarets are just behind us

We got there just after the opening time hoping to beat the inevitable queues from the tour busses as this is Istanbul tourist central. Our timing was perfectly coordinated with said coaches, and from the entrance in the south-west corner the queue stretched the length of the mosque, its courtyard, around the corner and half-way up the other side. We were offered expedited entry with a local tour guide for 40 lira (about £13) but being British we secretly like waiting in line and it only took 35 minutes.

Outside, the dark stone of its distinctive silhouette so iconic in Istanbul’s skyline looks fantastically detailed in bright sunlight, but seemed to make it one with the dreary overcast cloudy sky we had. This lowered our expectations for what we were about to find inside..

Inside the Sultan Ahmet Camii or Blue Mosque. The colours, light and shapes are almost too much for the senses!

The barriers separate the tourists from the worshippers as this is very much a working mosque. I thought the blue Iznik tiles of the first balcony were the reason for the name ‘Blue Mosque’, but it comes from the main dome..

Despite being restricted to the back 3rd of the main prayer hall, this, like so many times in Uzbekistan, was a “wow” moment. The space is huge, and dominated by the giant red carpet on the floor and the massive, beautifully decorated dome overhead. It’s the blue in the dome’s design that gives the mosque its name.

The main dome is decorated with stunning blue and gold painting, and this is why the mosque gets its name

Hippodrome

The central section of the Hippodrome hints at the greatness of this once mighty arena

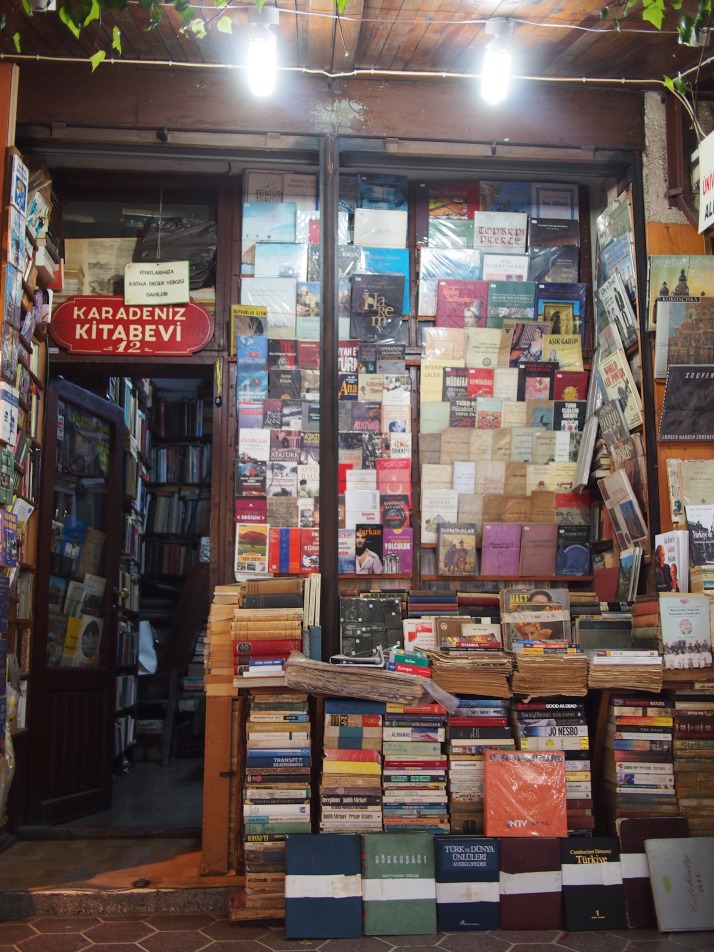

Just outside the Blue Mosque we stopped for an early packed lunch next to the massive Egyptian obelisk while we read the introduction to the Hippodrome from our guidebook.

Now a narrow park, it was really difficult to appreciate the sheer scale of the once mighty Hippodrome. Even when we read that the courtyard of the Blue Mosque was built on the foundations of the Hippodrome’s seating, we still weren’t able to fully appreciate how big and important this arena was to Byzantine society. In researching this post, I found this reconstructed image..

A computer generated reconstruction of the Hippodrome. The current park is about half the width of the chariot racetrack. The domes in the background are that of Haghia Sophia (source: Byzantine Military)

All that remains of the Hippodrome today are a fountain, 3 central columns, and the foundations of the western rounded end. The largest of the central columns is called, appropriately, Colossus, and having stood next to it in person, to then see it in situ as the middle-marker of the 30,000 seat capacity of the Hippodrome finally gave us a sense of scale.

The columns of the Hippodrome: the amazingly well-aged Egyptian obelisk that looks brand new; the bronze Serpent column which has seen many better days; and the Colossus, once covered in metal

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AjrnvDn2tcA]

Sokullu Mehmet Paşa Camii

Skipping a few of the smaller sights on the route, we arrived at another of Sinan’s mosques, Sokullu Mehmet Paşa. Built in 1571-2 on the site of a former church, we entered through a long outdoor corridor into the serenity of an empty courtyard and an all but empty mosque – a far cry from the bustle of the Blue Mosque earlier!

The lovely quiet courtyard of Sokollu Mehmet Paşa Mosque

We loved the quiet serenity of this mosque, and the 3 reasons why it features on the stroll:

- It’s built by Sinan, that automatically gets attention but as there almost 100 of his structures left that doesn’t guarantee a place. The book describes this as “one of the most beautiful of the smaller mosques of Sinan“

- The Iznik tiles in the mihrab are exquisite, and

- There are 3 fragments of black stone from the Kaaba in Mecca embedded into the walls: one above the main entrance, another above the entrance to the mimber and the last in the centre of the mihrab

Sneaky picture of Sokollu Mehmet Paşa Mosque while the imam was telling someone else off for taking photographs. The fragments of the Kaaba from Mecca are too small to see in the photo, but they’re just below the panel of writing on both the mihrab and the mimber

Namazgah

Namazgah of Esma Sultan. Nice, but what’s it for?

At first glance we weren’t sure we’d found what we were looking for when we entered a small park and children’s play area and spotted an old stone square fenced off in the corner. On closer inspection it was, as our book describes, the last remaining namazgah within the city walls, and one of 3 left in Istanbul.

So what is it? Well, a namazgah is an outdoor prayer area. We thought it was a really interesting thing to see, and it was a shame we couldn’t get closer than the surrounding fence.

SS Sergius & Bacchus

The lovely light interior of the former Byzantine church of SS Sergius & Bacchus

Approaching the sea, but not yet past the defence of the sea walls, we arrived at SS Sergius & Bacchus, which, like many of the mosques in Istanbul was once a Christian church and subsequently converted to a mosque. Our guidebook introduces it thus:

“SS. Sergius and Bacchus were two Roman soldiers martyred for their espousal of Christianity; later they became the patron saints of Christians in the Roman army. These saints were especially dear to Justinian because they saved his life some years before he came to the throne, in the reign of Anastasius. It seems that Justinian had been accused of plotting against the Emperor and was in danger of being executed, but Sergius and Bacchus appeared in a dream to Anastasius and interceded for him. As soon as Justinian himself became Emperor in 527, he expressed his gratitude to the saints by dedicating to them this church, the first of those with which he adorned the city.” – Strolling through Istanbul, p123

Just like Sokullu Mehmet Paşa earlier, we found SS Sergius & Bacchus to be quiet, and we were encouraged to do something we’ve wanted to do in every mosque we’ve visited with an internal balcony – go upstairs!

Us inside the Church of SS Sergius & Bacchus, now known as Küçük Aya Sofya Camii – which means “Little Haghia Sofia”

The late afternoon light through the windows was lovely, we loved the light airiness of the decoration and the luxurious sky-blue carpet which felt decadent to walk on.

Byzantine Sea Walls and the Palace of Bucoleon

All that remains of the Palace of Bucoleon, one of the seaside buildings of the Grand Palace of Byzantium

The route then ducks under the railway lines which once carried the Orient Express, and through the old sea wall defences to highlight some of the oldest parts of the city.

The highlight of this section for us was the huge marble window frames of the Palace of Bucoleon, which was part of the original Grand Palace of Byzantium, once the heart of Constantinople, and sadly all that remains of it above ground. Even though little of this palace remains, it gave us a sense of scale and grandeur.

After the Palace, we passed ruins of old gates into the city, a marble pavilion and the foundations of an old church. A lot of the old vaulted sub-structures and gatehouses are being used for temporary shelter, and while we felt perfectly safe wandering along the sea walls, the smell of impromptu toilets did prevent us from inspecting some of the vaults more closely.

The massive vaulted sub-structures of the church of St. Saviour Philanthopes. I’m just working out if I can get out once I get in; yes I can, and here’s the view from inside. This was the largest open one we found at 4 chambers wide

Grand Palace Mosaic Museum

The entrance to the Grand Palace Mosaic Museum behind the Blue Mosque, not a mosaic in sight.. yet..

The walk ended just behind the Blue Mosque at the Mosaic Museum, which doesn’t look much from the outside but it’s mentioned briefly in our guidebook, and the reviews we’d read elsewhere highly recommended it.

The first room of the Great Palace Mosaic Museum. We weren’t expecting so many mosaics!

After passing an unkempt garden of old stone columns and capitals, we entered what looked like a temporary shed and found ourselves on a 1st floor catwalk overlooking the restored mosaic peristyle of the Grand Palace.

Thought to date from Justinian’s reign (527-65), and believed to be the floor of the north-east portico of the Grand Palace, the mosaics were uncovered during excavations in 1935 and have since been restored a couple of times.

Collage of mosaics from the Great Palace Mosaic Museum. Clockwise from top-left: most of the scenes are of hunting, either humans hunting animals or animals hunting animals like this Eagle with a rodent; A bear feeding on a deer; the head of a boy at play; a very intricate and colourful section of a border; and two boys with a bird riding an ox

The mosaics are wonderful – we weren’t expecting such detailed work or such an extensive collection. The most recent restoration effort is explained in fascinating detail along with what is known about their history in panels throughout.

It was a nice end to another day of strolling, and something quite different to mosques and old walls.

two year trip

two year trip