The Fergana valley is the easternmost part of Uzbekistan. It is incredibly rich and fertile farmland and has the highest proportion of ethnic Uzbeks in the country. As we travelled around Uzbekistan we met lots of friendly people and it seemed that, disproportionately, when we asked them where they were from they mentioned one of the cities in the Fergana valley. It is perhaps unsurprising then that here we were overwhelmed by meeting some the most friendly, generous and hospitable people in Uzbekistan – a country that overall we’ve found to be incredibly welcoming!

The beautiful view from the mountain pass between Tashkent and Fergana

The beautiful view from the mountain pass between Tashkent and Fergana

To get to Fergana from Nukus in the far west of the country where our trip to the Aral Sea ended, we needed to go via Tashkent. It’s possible to fly, but we had time and a hankering for the Russian trains that we had experienced over a year earlier near the beginning of this trip so we bought tickets for the overnight train to the capital and were excited to find out that it originated in Saint Petersburg!

Happy to be back in a Russian train

Happy to be back in a Russian train

The railways were built during Soviet times and much of the rolling stock dates from that period so it was very similar to how we remembered except that this time the carriage seemed to be full of Uzbeks who’d been shopping in Russia. The guy across the way from us was sharing his bunk with two huge TV sets, and one couple had boxes and boxes of stuff, far more than they could carry.

Sharing a bunk with two brand new TVs – one propped in front of the window and one taped to the bunk above!

Sharing a bunk with two brand new TVs – one propped in front of the window and one taped to the bunk above!

After an overnight stay in Tashkent, we then had to navigate the journey to Fergana which turned out to be a bit of a marathon. First we had to get a mashrutka, or minibus, from Chorsu Bazaar, near our guesthouse, to Kuyluk Bazaar, 20km outside the city, where the shared taxis to the eastern cities congregate. Then we had to find the shared taxis to Fergana (harder than we’d expected), negotiate a price for the trip and wait in a swelteringly hot car while the driver rustled up passengers for the other seats (that’s the shared bit; buses are not permitted on the mountain roads so regular cars are used to move people back and forth).

Andrew surrounded by taxi drivers at Kuyluk Bazaar, at this point we were trying to work out where the shared taxis left from

Andrew surrounded by taxi drivers at Kuyluk Bazaar, at this point we were trying to work out where the shared taxis left from

Eventually we set off, Andrew quickly made friends with the guy sitting next to him, chatting in a combination of broken Russian, broken English, sign language and diagrams. There were numerous stops; we were given a yoghurt drink to try, bought bread from what appeared to be a bread and melon market beside the highway in the middle of nowhere, and met a group of Spanish construction workers at a truck stop ruing the food they had to put up with while working on a new road in the mountains. At the final stop before we reached Fergana city, the driver took us through his home town of Oltiarik where we met his grape farmer friend who cut three massive bunches of grapes straight from the vines and presented them to us. Wow, what a journey!

Shared taxi from Tashkent to Fergana (clockwise from top left): Julie trying a local yoghurt drink; view of the mountains we had to cross; we bought delicious bread from this lady; grape farmers with just one of the three bunches they gave to us

Shared taxi from Tashkent to Fergana (clockwise from top left): Julie trying a local yoghurt drink; view of the mountains we had to cross; we bought delicious bread from this lady; grape farmers with just one of the three bunches they gave to us

We arrived in Fergana quite late in the afternoon and worn out from all the travelling so we decided to take it easy on the following day. We had a lie-in, ate some of our mountain of grapes for breakfast and then set off to the bazaar to have a look around. It was an interesting place, stuffed with tons of fresh produce as you would expect for a farming area in September.

Fergana Bazaar (clockwise from top left): butcher in the open air; girls selling carrots; huge pumpkins; this cobbler glued the soles of my sandals back together and refused payment

Fergana Bazaar (clockwise from top left): butcher in the open air; girls selling carrots; huge pumpkins; this cobbler glued the soles of my sandals back together and refused payment

Just as we were trying to work out where to eat lunch, we were approached by a local man. His name was Habib and, during the usual chit-chat, we found out that he learnt his excellent English while working in London for a while before returning home to open a pharmacy and a cafe. He found out that we wanted to try the local plov as we’d been told that Fergana’s version of the national dish was especially good and he set off with us in tow eager that we should only try the best. We were a bit worried that we were messing up his plans for the day but by now we’ve learnt that in these situations we just have to submit. After trying several places and asking advice from a number of locals he settled on a particular restaurant before joining us and paying for our meal! After eating, we assured him that we could manage to make a few purchases in the market without help, and he left us with his phone number and directions to his cafe in case we needed anything.

Fergana’s version of plov is made with brown rice

Fergana’s version of plov is made with brown rice

After lunch we’d intended to explore some more but unfortunately the wind picked up causing a dust storm in the centre of town so we retreated back to our guesthouse

After lunch we’d intended to explore some more but unfortunately the wind picked up causing a dust storm in the centre of town so we retreated back to our guesthouse

The next morning, we took the bus to the nearby town of Margilon which is the centre of silk production in Uzbekistan, the 3rd largest silk producer in the world. The Lonely Planet informed us that the Kumtepa Bazaar which runs only on Sundays and Thursdays was a good place to get a local vibe and see the silk being sold by the metre. I’m not sure quite what we expected but it certainly wasn’t the massive hive of activity selling everything from leather boots to car tyres to melons that we found.

Melon sellers line the approach road to Kumtepa Bazaar

Melon sellers line the approach road to Kumtepa Bazaar

Before we ventured into the market proper we wandered along the roadside. Firstly because as the minivan had passed we’d seen mountains of melons for sale from the boots of cars and we wanted a closer look, and second because we’d spotted some seriously heavily loaded cars and thought we might find a good vantage point to take some photographs. Most of the cars in Uzbekistan are either small Daewoo Matiz or a Chevrolet saloon model called Nexia, but whenever we’ve seen a car with a heavy load it has always been an old Soviet model, usually a Lada. Here was no exception with massive loads of furniture balanced precariously atop and in the boot.

Laden ladas outside Kumtepa Bazaar

Laden ladas outside Kumtepa Bazaar

This baker beckoned us into his shop and we watched enthralled as he shaped and baked the bread – you can just see the loaves stuck to the inside of the oven in the background

This baker beckoned us into his shop and we watched enthralled as he shaped and baked the bread – you can just see the loaves stuck to the inside of the oven in the background

Finally we entered the central market area. I don’t think too many tourists get out this way because, like the markets that we visited in Bangladesh, people were extremely curious, chatty and welcoming. Like Bangladesh, Uzbekistan is a Muslim country and, in the traditional Muslim culture, it’s not unusual for men to direct all questions to Andrew, want their photo with him and not even shake my hand; all done with extreme respect and courtesy, and occasionally advantageous as while I’m being ignored I can be taking photos of interesting stuff, but still it’s a bit tiresome after a while. In Margilon there were at least as many women vendors as men and probably more women customers and so I got a lot of interest and interaction too.

Julie sharing a joke with the ladies at the entrance to the bazaar. They were selling the traditional hats called Tubeteika or Duppi so of course I had to try one too!

Julie sharing a joke with the ladies at the entrance to the bazaar. They were selling the traditional hats called Tubeteika or Duppi so of course I had to try one too!

There were just a few aisles dedicated to the silk but it was spectacularly beautiful

There were just a few aisles dedicated to the silk but it was spectacularly beautiful

Stalls are grouped by the type of goods being sold. One of the first sections that we walked through was selling leather boots

Stalls are grouped by the type of goods being sold. One of the first sections that we walked through was selling leather boots

We though we had reached the edge of the bazaar when we rounded a corner to find a huge area devoted to tyres and other spare parts for cars

We though we had reached the edge of the bazaar when we rounded a corner to find a huge area devoted to tyres and other spare parts for cars

This lady asked me to take her picture then Andrew made her laugh

This lady asked me to take her picture then Andrew made her laugh

There was a big area behind the main market selling the furniture that we’d seen loaded onto cars at the front. Inside we found a carpet section to complete the home decoration.

There was a big area behind the main market selling the furniture that we’d seen loaded onto cars at the front. Inside we found a carpet section to complete the home decoration.

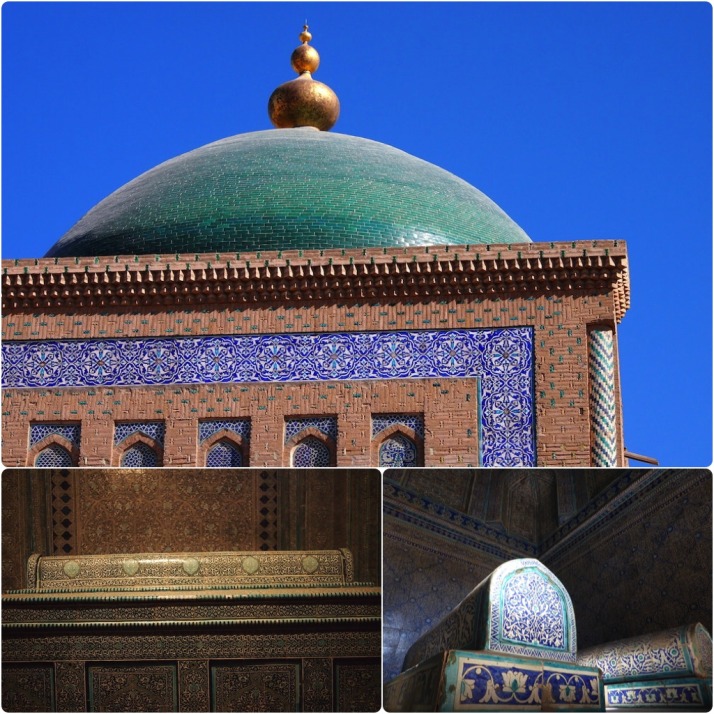

Having reached the farthest end of the bazaar, we spotted a kebab stand and took a seat set back out of the way for a bite of lunch when a man saw us, stepped into the cafe, smiled and said ‘Samarkand’, remarkably he was one of the friendly local tourists we’d met at Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand. Excitedly he pulled up a photo of him and his friend with Andrew on his phone while I found the corresponding shot on my camera! Crazy that we could come halfway across the country and meet again by chance. We took another photo to prove the coincidence and turned down his kind offers to take us to his house for food.

At Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand above, and below at Kumtepa Bazaar in Margilon

At Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand above, and below at Kumtepa Bazaar in Margilon

We agreed that Kumtepa Bazaar was one of the friendliest and most interesting markets we’ve ever been to, and well worth the long trip from Tashkent.

two year trip

two year trip