Uzbekistan is the first country either of us have visited in Central Asia. Why did we chose Uzbekistan? Well, we were looking for somewhere to visit enroute from China to Europe as we make our way homeward towards the UK, and as the old Silk Road went right through it we knew it would be steeped in history.

More recently, it used to be part of the old Soviet Union which meant we could dust off the little Russian we already know while trying to pick up the odd word of Uzbek.

Chorsu Bazaar

The lovely tiled dome of Chorsu Bazaar is but the dusty tiled tip of this immense iceberg of a market

Chorsu Bazaar is the bustling heart of Tashkent. We love visiting markets anyway, so Chorsu was high on our list and after a few hours wandering through it, we think it’s a strong contender for the best market we’ve visited.

Inside the cool Chorsu dome are the various meat counters set out in concentric rings

This guy asked for his photo as he was restocking one of the butcher counters with fresh meat

The icon of Chorsu bazaar is the wonderful turquoise tiled domed hall that sits in the north-west corner and houses the meat market. Outside, we found rows of rice and spice sellers, rows of beautifully ripe vegetables – including tomatoes the size of baking apples – and trucks full of melons and watermelons! Further, we found household goods, shoe repairs, a high street-like two storey row of clothing shops and stalls and a cafe area. It was then we realised the dome is but a fraction of the size of this sprawling hub of sights, smells, tastes and trades.

Rows upon rows of fresh produce, like this one of potatoes

There were echoes of our experiences in Bangladesh markets where the traders would beckon us over wanting their photograph taken or for us to pose with them!

In a quiet corner of the bazaar, our good friend Jo (whom you might remember joined us in Vietnam last year) was roped into a photo while buying some dried apricots

Kulkedash Medressa

The Kulkedash Medressa sits on a hill in the south-eastern corner of Chorsu Bazaar, and is where the busses drop off from the airport

The Kulkedash Medressa is a welcome slice of serenity after the claustrophobic bustle of Chorsu Bazaar. Medressa translates as school, and is akin to our higher education or university system; students learn a wide syllabus of sciences and Islam.

The lush serenity of the Kulkedash Medressa courtyard

As well as teaching rooms and student accomodation, teachers have small offices and as we walked around a few of them were open. When we popped our heads around the door of the calligraphy room, the friendly gentleman inside came to the door and invited us in. His English was excellent, and after he showed us the various styles of Arabic script, including a mosaic style used on minarets and diagonal diamond patterns, he wrote Julie’s name in Arabic on a scrap of paper!

Calligraphy teacher writing Julie’s name in Arabic. He explained that he travels quite a bit to advise the decorative restoration and construction work of Islamic buildings within Uzbekistan

Amir Timur Square

Statue of Amir Timur, the national hero of Uzbekistan

Born around 1330, Amir Timur is the Central Asian Chinggis Khan – regarded as a military genius and tactician who sought to reunify the great Khan’s empire, his Tirmurid dynasty extended from southeastern Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran, through Central Asia encompassing part of Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and bordered Kashgar in China.

Today, he’s regarded as the national hero of Uzbekistan and his statue dominates Tashkent’s central square. It’s pretty much the only thing here save for a few fountains and as there’s little shade we didn’t stay for long.

Independence Square

The gates to Uzbekistan’s Independence Square

A couple of blocks away from Amir Timur is the country’s Independence Square, where fountains abound and giant square gates are adorned with silver pelicans said to bring good luck. The independence celebrated here is from the former USSR, Uzbekistan was one of the first countries to declare their independence when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Tashkent’s Crying Mother statue in remembrance of the Uzbek soldiers who fought in World War II

Facing us across the square is the giant statue of a Crying Mother who commemorates the 400,000 Uzbek soldiers who died fighting with the allies in World War II. Having such a imposingly powerful memorial here gave me a strange sense – perhaps it’s meant as a reminder that independence is hard won but worth fighting for.

Khast Imom Square

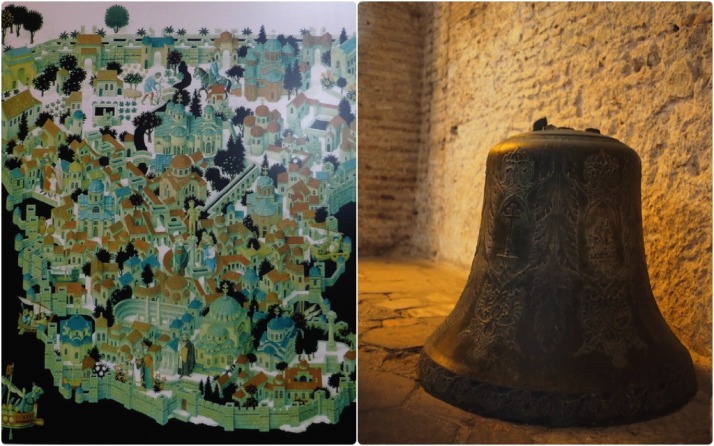

Khast Imom Square. From left (east) to right (west, through south): Hazroti Imom Friday Mosque; Moyie Mubarek Library Museum; Telyashayakh Mosque; Barak Khan Medressa

It won’t be much of a spoiler to tell you right now, that one of the three words we’ll be using to describe Uzbekistan in our Round Up we both said out loud when we first saw the Khast Imom Square.. “Wow.”

Julie and I in front of the Barak Khan Medressa

This is the official religious centre of Islam in Uzbekistan. To the east of the square is the Hazroti Imom Friday mosque, to the west is the Barak Khan Medressa which used to be a centre of learning until the student rooms filled up with souvenir stands.

According to our guidebook there is a third building called the Moyie Mubarek Library Museum that houses the Osman Qur’an (Uthman Qur’an), the oldest known copy of the Qur’an. I thought it might be the small, squat building in the square, but Julie thought it was the grand, wooden pillar-fronted one to the north. We poked our heads into the latter to find what looked like a doctor’s waiting room, and received a very puzzled look from the handful of people sitting inside. We translated the sign on the outside and deduced it was, in fact, a family planning clinic!

It took a bit more wandering before Julie decided that it might be worth a look in the small squat building in the square. The one with the short fence and the security box outside.

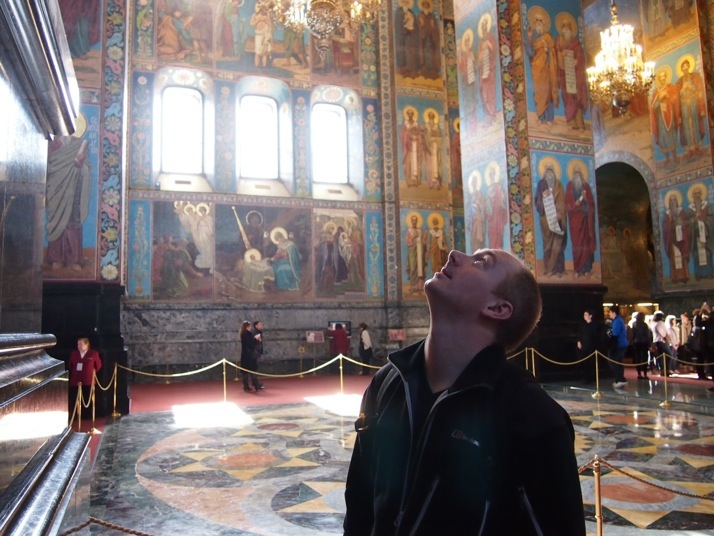

We paid 6,000som each (about £1.20) to the guard inside the building, and taking centre stage, is reportedly the oldest Qur’an in the world.

The Osman Qur’an (Uthman Qur’an), said to be the oldest in the world. A few pages are missing, and we overheard a guide say that there’s a page in the British Museum (photo source: Bruce Loeffler)

Its pages are about a foot square, made from deerskin and written in old Arabic script. Even with a few pages missing, it weighs about 40kg.

Our guidebook tells us a little of its history..

This enormous deerskin tomb was brought to Samarkand [in Uzbekistan] by Amir Timur, then taken to Moscow by the Russians in 1868 before being returned [to Tashkent] by Lenin in 1924 as an act of goodwill towards Turkestan’s Muslims. – Lonely Planet, Central Asia, p147

Peeping through the door into the Hazroti Imom Friday Mosque. We were allowed to enter the courtyard and look through the windows but we weren’t allowed into the mosque itself

The library has many more examples of the Qur’an, including a couple of tiny ones with pages smaller than postage stamps, and a display of translations into different languages.

Museums

Fine Arts Museum of Uzbekistan, not much to look at from the outside but definitely worth the visit

Like any capital city, Tashkent has a good number of museums though most get lukewarm write-ups and of the ones we decided to visit we found the quality was a little variable.

First up was the Fine Arts Museum of Uzbekistan which we really enjoyed. Each of the 4 floors are partitioned into small, easily digestible rooms and the whole place is chronological from the ground up, starting with 7th century Buddhist relics, through Uzbek crafts such as block printing and silk production, to Russian paintings and sculpture inspired by the European Renaissance.

The House of Photography, described as “edgy” by the Lonely Planet may have lost its edge

We love photography museums because we like taking photographs and they’re great for ideas and inspiration. Not so much Tashkent’s House of Photography which, while very cheap, had one display of aerial shots of Uzbekistan akin to those you might find in a tourism brochure, and the other two were probably what I’d shoot if you gave me an expensive DSLR for a day – in focus, good detail, but standard subjects, composition and nothing memorable. Still, at only 10p to get in it was worth the punt, and there wasn’t an extra charge for taking photographs.

Mobbed by a class of school kids as we made our way into the History Museum of the People of Uzbekistan

Last on our short list was the History Museum of the People of Uzbekistan, which we were lucky to get into at all as it must be a prerequisite school-trip!

It’s essentially a history museum of Uzbekistan from ancient Turkestan to the present day and, while a little heavy going in places, and a little bereft of English captioning on recent events it was a good over-arching introduction to the people and dates that shaped the country.

Orthodox Assumption Cathedral

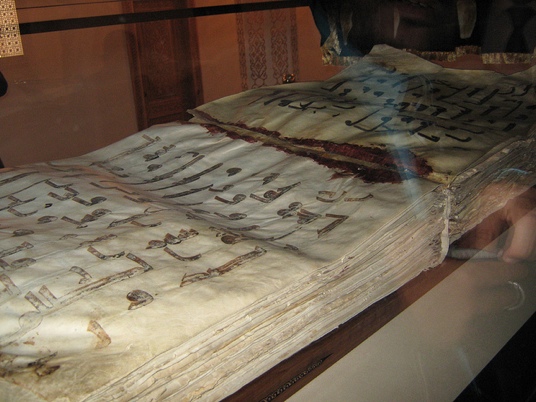

The Assumption Cathedral in Tashkent reminded us of the many Orthodox churches and cathedrals we visited in Russia

We loved visiting the massive Orthodox churches and cathedrals in Russia, especially the Church on Spilled Blood in St Petersberg and the golden domes of the The Church of All-Saints Resplendent on Russian Land in Yeketerinberg, which we were reminded of when we saw Tashkent’s Assumption Cathedral.

The golden domes are topped with very ornate crosses

With the balmy weather, Julie and Jo had forgotten their headscarves, but were able to borrow one so we could take a look around inside. We didn’t take any pictures as there were people worshipping, except for one at the entrance..

Julie and Jo in borrowed headscarves

Valletta’s southern walls meet the sea

Valletta’s southern walls meet the sea The exterior of St John’s Co-Cathedral is rather plain and currently undergoing restoration

The exterior of St John’s Co-Cathedral is rather plain and currently undergoing restoration The spectacular nave with its painted ceiling

The spectacular nave with its painted ceiling The High Altar is the centrepiece of the interior

The High Altar is the centrepiece of the interior Chapel of Aragon; we weren’t sure exactly where Aragon was and were interested to find that it is an autonomous community in northern Spain

Chapel of Aragon; we weren’t sure exactly where Aragon was and were interested to find that it is an autonomous community in northern Spain Chapel details (clockwise from top left): tomb in the French Chapel; even the ‘plain’ walls are covered with gilded carvings; altar in the Italian Chapel; Spanish Chapel altarpiece

Chapel details (clockwise from top left): tomb in the French Chapel; even the ‘plain’ walls are covered with gilded carvings; altar in the Italian Chapel; Spanish Chapel altarpiece Inlaid marble gravestones cover the floor of St John’s Co-Cathedral

Inlaid marble gravestones cover the floor of St John’s Co-Cathedral

two year trip

two year trip