We like to learn about the places we travel to and a visit to the country’s museums can often be a good way to do that. However in many areas of the world which are not as affluent as Western / Northern Europe, exhibits can sometimes be a bit tired or dusty, with difficult to read translations, if any. But not so in Georgia, we were consistently impressed by the quality of the museums with well laid out displays, professional lighting and coherent and informative English labelling.

Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi: Andrew checking out the well-lit and labelled displays; an early 19th century Persian painting of a girl with a tambourine (artist unknown)

The centre piece museum is without a doubt the Museum of Georgia in Tbilisi. The exhibitions ranged from Asian art to Georgia’s time under Soviet occupation to a fascinating gallery filled with skulls and skull fragments of human ancestors from the Stone Age. But the standout exhibit has to be the Archaeological Treasury filled with beautifully made golden grave goods from burials excavated in Georgia and dating back to the 3rd millenium BC. The side room containing the numismatic treasury was cleverly set up with two examples of each coin (where possible) one showing the face and the other the reverse.

The progression of skull shapes through hominid development, Stone Age exhibition in Museum of Georgia

Coins and intricate goldwork in the Archaeological Treasury of the Museum of Georgia in Tbilisi, including the lion statuette which we recognised as the logo of the Bank of Georgia

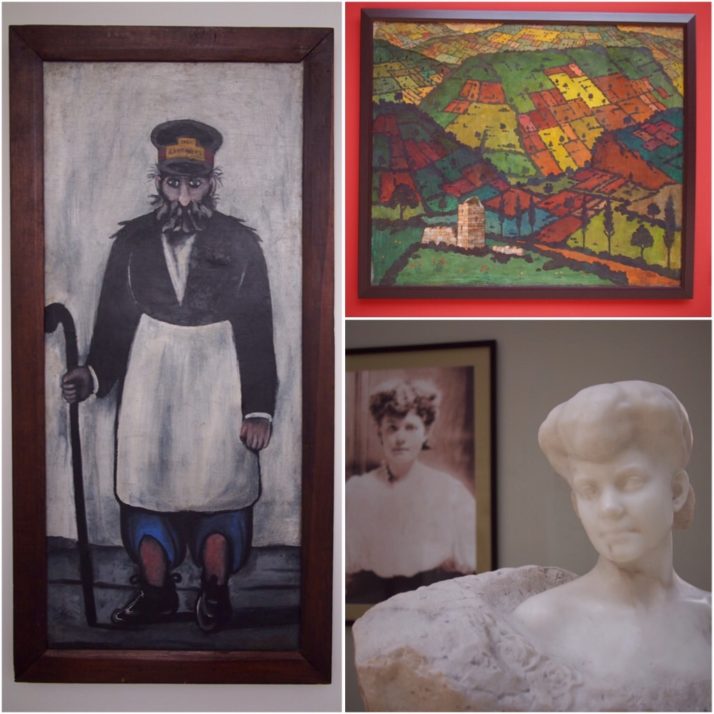

The regional museums had nice twists showcasing what is special to their area of the country. The museum in Sighnaghi had a fairly standard exhibit of the archaeology and development of the area, but upstairs was a gallery of paintings by locally born national painter Niko Pirosmanashvili, also known as Pirosmani. We saw more of his pictures along with other Georgian artists in Tbilisi’s National Gallery.

National Gallery, Tbilisi (clockwise from left): ‘Yard Cleaner’ by Niko Pirosmanashvili; ‘Imeretian Landscape 1934’ by David Kakabadze; ‘Girl from the North’ by Iacob Nikoladze

In Svaneti the museum in Mestia is recently reopened in a state of the art building and displays many treasures from the region’s churches alongside culturally specific Svan items including clothing, weapons and local crafts.

The Svaneti History and Ethnography Museum in Mestia reopened in 2013 in this custom-built modern building

Svaneti History and Ethnography Museum (clockwise from top): icons from Svaneti’s churches; photograph of a late 19th century sanctuary door by Vittorio Sella; traditional Svan snow shoes

The final museum that we visited in Georgia is not under the aegis of the Georgian National Museums body, it is devoted to the country’s most infamous son, Josef Dzhugashvili, better known as Joseph Stalin. Stalin was born in Gori, 80km west of Tbilisi, and the museum contains the house where he was born and spent the first four years of his life, preserved on the spot where it originally stood, covered by a pavilion adorned with a Soviet hammer and sickle. The custom built museum is rather grand but slightly shabby and very cold, reminiscent of the Museo de la Revolucion in Havana. Its construction was actually started in 1951, two years before Stalin’s death, but didn’t open until 1957.

Stalin’s birthplace is preserved at the Stalin Museum in Gori

The displays were not particularly well signed but the whistlestop guided tour (included in the admission fee) was good at highlighting notable artefacts and giving an overview of the arc of Stalin’s life. For a man who is generally reviled in the west, it was strange to be in a place where the atrocities commited during his time in charge of the USSR are hardly acknowledged, the small corner devoted to those who died under his rule felt like a very token effort.

Stalin Museum (clockwise from top left): grand entrance staircase; the museum contains a large collection of photographs, letters and busts of Stalin; Stalin’s armoured train carriage contains a bathtub and an early air conditioning system; I was quite taken with the several carpet portraits

Somehow the gift shop at the Stalin Museum manages to be tacky and slightly disturbing at the same time

two year trip

two year trip