As we knew Julie’s sister and family were coming out to join us, we held off visiting two of the best and most exciting sites in Istanbul so we could experience them with Steph, Tom and two-year-old son Oliver.

Haghia Sophia

Haghia Sophia – built as an orthodox cathedral in 537, had a brief 57 year stint as a roman catholic church starting in 1204, converted to a mosque in 1453 and finally a museum in 1935

Nearly 1500 years old, Haghia Sophia has seen the pinnacle of the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, held the title of the largest cathedral in the world for a thousand years, and has dominated the Istanbul skyline of the First Hill since it was completed in 537.

The present Haghia Sophia is the 3rd church of that name to have been built on the site, the first two burnt down during separate riots; the first one in 404, and the second in 532. This 3rd one, completed in 537 was rebuilt on the order of Justinian, who envisioned it on an even grander scale than those before.

Haghia Sophia was an Eastern Orthodox cathedral and the seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, except for a brief period between 1204 and 1261 when it was converted to a Roman Catholic cathedral under the Latin Empire. When Sultan Mehmet II took Constantinople in 1453 he converted it to a mosque, and in 1931 the doors closed for worship, opening 4 years later in as a museum in 1935.

The entrance walks you past excavated remains of the previous structure on this site – the Theodosian Haghia Sophia built in the 5th century which burnt down during the Nika Revolt in AD 532

Haghia Sophia is a massive building that, when we first saw it, we wondered what all the fuss was about because, well, I’ll just say it; it’s not very attractive to look at. The intricate dome looks like it has been dropped on some hulking, unfinished, fortress-like structure. It’s only when we learnt that the unsightly rose coloured buttresses were added in 1317 to prevent the weight of the dome from pushing the walls out and causing the whole thing to collapse, that we could start to see the building without its protective concrete corset.

The entrance to Haghia Sophia is through one of the 5 western doors into the exonarthex. The massive central door on the left was known as Orea Porta or the Beautiful Gate and was reserved for the Emperor

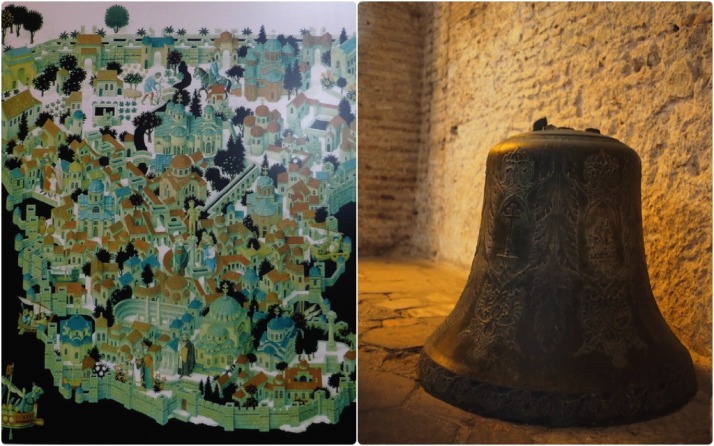

There are two narrow narthexes (or porches) which mark the entrance to the Haghia Sophia. The first one is quite plain and giant posters give an extremely brief summary of the building’s history, though one of them does show a nice illustration of ‘Constantinopolis’ when the Hippodrome still existed.

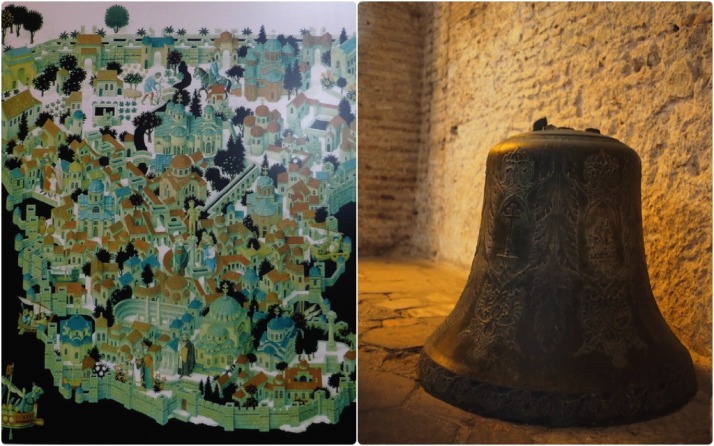

This exonarthex also has a few artefacts on display such as a large bronze Christian bell and a sarcophagus believed to belong to Empress Eirene, wife of Emperor John II (r. 1118 to 1143).

Our favourite of the displays in the exonarthex, an illustration of Constantinopolis that shows Haghia Sophia in its original Orthodox Christian church for (bottom centre), the Hippodrome and the aqueduct, and the city surrounded by the Theodosian walls; the bronze bell with Greek inscriptions and Christian crosses

From the exonarthex we passed through the Emperor’s Beautiful Gate and into the narthex, which gave us the best impression of what the newly completed Haghia Sophia would have looked like – according to records, the ceiling of the entire church was covered in gold mosaic tiles and geometric and floral designs, an area of more than 4 square acres – that’s over 16,000m2 or about 2½ football pitches!

This amazing ceiling was rediscovered in 1933. When it was converted to a mosque the mosaics were plastered over – thank goodness they weren’t destroyed

At the end of the narthex is a small corridor known in Byzantine times as the Vestibule of Warriors which is now the public exit, and hung above the bronze-clad doors is a giant mirror so you don’t miss another golden mosaic they found under the plaster and whitewash in 1933..

Mosaic of the Mother of God holding the Christ Child and flanked by Constantine the Great on the right offering a model of Constantinople, and Justinian on the left offering a model Haghia Sophia

We backtracked into the narthex and stepped through the Imperial Gate into the vast open nave..

Julie standing in the Imperial Gate – the Emperor’s door from the narthex into the nave of church. Just how big were these Emperors?!

To borrow our word from Uzbekistan.. Wow.

Wow. Standing in the nave is to be dwarfed by the sheer scale of the space and the mighty dome

Even the size of the Emperor’s gates just didn’t prepare us for the sheer scale and architectural achievement of Haghia Sophia. The effect is a huge, almost square open space uncluttered by supporting columns, that stretches so high that the size of the dome is nearly lost as an optical illusion. The crown of the dome is 56 metres from the floor – the equivalent of a 15 storey building!!

The dominating dome of Haghia Sophia

We took our time to explore this resplendent, religiously repurposed super-structure. The Islamic adornments seemed both at home with their extravagant design, but at the same time looked temporary, a bit like birthday party decorations. I guess that’s because the restoration has uncovered the Christian mosaics which makes the museum theologically schizophrenic.

In the nave we loved the mighty marble supporting columns so cleverly engineered to maximise the space which make the dome appear almost unsupported. Also the two lustration (ritual purification) urns either side of the entrance that are hewn from single blocks of marble.

One of the two huge marble lustration urns that were brought from Pergamon during the reign of Sultan Murad III (r. 1574 to 1595)

After turning our thumb through 360° in the hole on the weeping column which is believed to cure many illnesses, we headed upstairs to the galleries. A few more golden mosaics have been rediscovered along the galleries, but we liked the Marble Door, and the view past the türbes outside to Sultan Ahmet Camii or The Blue Mosque

The Marble Door. We’re not sure if the name comes from the door in the middle, or that either side are double-doors representing Heaven and Hell

Sultan Ahmet Camii (The Blue Mosque) in the background, past the domes of 3 of the türbes in the grounds of Haghia Sophia

Despite the lacklustre first impression, we really enjoyed exploring the expansive Haghia Sophia. Describing it as a museum doesn’t really set the right expectations either, as there isn’t a lot of information about it inside – this is one of those places that the more you read about it the more impressive it becomes, and the more you understand the reverence in which it is held.

Basilica Cistern

The Basilica Cistern, 9,800m2 in size, can hold 80,000 cubic metres (2,800,000 cu ft) of water, and was forgotten for nearly a hundred years!

When we were researching what to see and do in Istanbul, we read the almost incredulous story of the rediscovery of the Basilica Cistern. To quote our guidebook..

The structure was known in Byzantium as the Basilica Cistern because is lay underneath the Stoa Basilica, the second of the two great squares on the First Hill. The Basilica Cistern was built by Justinian after the Nika Revolt in 532, possibly as an enlargement of an earlier cistern of Constantine. Throughout the Byzantine period the Basilica Cistern was used to store water for the Great Palace and the other buildings on the First Hill, and after the Conquest its waters were used for the gardens of Topkai Sarayi. Nevertheless, general knowledge of the cistern’s existence seems to have been lost in the century after the Conquest, and it was not rediscovered until 1546. In that year Petrus Gyllius, while engaged in his study of the surviving Byzantine antiquities in the city, learned that the people in this neighbourhood obtained water by lowering buckets through holes in their basement floors’ some even cause fish from there. Gyllius made a through search through the neighbourhood and finally found a house through whose basement he could go down into the cistern, probably at the spot where the modern entrance is located. – Strolling Through Istanbul (p135)

Steph and Julie queueing in the howling, miserable rain while Tom and I look after Olly in the shelter of the modern entrance. Perfect weather for going underground..

Descending 100m into the cistern, we were greeted by rows upon rows of marble columns, now standing in a reservoir of about half a metre of water. And yes, there are still plenty of fish, their ghostly shadows cast by the uplight against the pillars. People take food down there for them, and as I guess they’re no longer caught, there are some monsters lurking under the walkways!

When the fish weren’t around the reflections of the columns and the vaulted ceiling where lovely

Besides the spectacle of the cistern itself, there are 3 columns to look out for along the route. The first is a column repurposed from the now long gone Triumphal Gate of the Forum of Theodosius I – the distinctive peacock eye relief stands out against all of the other smooth columns.

The second and third are two ancient classical bases that can breathe after centuries underwater. These are depictions of Gorgons, which in Greek mythology are 3 sisters, one of whom you’ll undoubtedly have heard of – Medusa – and indeed she is touted as one of the heads, though according to the legend all three sisters had hair made of living, venomous snakes.

Column details in the Basilica Cistern, from left to right: Supporting column originally from the triumphal arch in the Forum of Theodosius I; The Medusa head Gorgon base which is inverted because it is said to negate the power of the gaze; The second Medusa base, this one rotated which also counts as a negating strategy

Like Haghia Sophia, we really enjoyed the Basilica Cistern (and dodging the awful weather outside was a bonus!) – they’re both larger than we thought they’d would be, even having read about them before we visited. Indeed, the Basilica Cistern even has a small cafe!

Us at the Cistern Cafe in the Basilica Cistern. We didn’t buy anything but the coffee smelled good

two year trip

two year trip